The misleading math of a startup wealth tax

An Excel butterfly flaps its wings.

For people wondering how to pay for Biden’s $1.9 trillion economic aid package, Elizabeth Warren has a plan: Last week, she proposed creating an annual 2 percent tax on the net worth of anyone with more than $50 million in assets, with an additional 1 percent tax on anyone worth over $1 billion. According to Warren, the legislation would raise $2.75 trillion over ten years.

Though the plan is supported by a majority of Democrats and Republicans, Silicon Valley’s venture class responded to similar proposals with predictable denouncements. A wealth tax reduces the upside of a starting a successful company; a wealth tax dilutes the amount of control founders’ have over the companies they start; a wealth tax shrinks the pool of angel investors who can fund “innovation;” a wealth tax would push startup employees worth tens of millions of dollars to the brink of bankruptcy, bankruptcy they “will have to forfeit shares” (i.e,, their wealth) to stay out of, which, well, seems like the whole point of a wealth tax.

In a short post from last summer, YC founder Paul Graham put some numbers to his argument. According to Graham’s math, a successful startup founder would lose 65 percent of their wealth to Warren’s tax plan over the course of their life. (Graham excludes the billionaire surcharge in his calculations; for consistency, my model excludes it as well.) The number seems striking, especially when compared to Warren’s description of the plan as a modest “two cent tax.”

Graham’s number isn’t wrong—it’s irrelevant.

Graham presents his calculations as representative of a “successful startup.” And at first glance, his assumptions sound reasonable enough: A founder starts with $2 million dollars worth of equity in their company. Their shares grow “3x for 2 years, then 2x for 2 years, then 50% for 2 years, after which you just get a typical public company growth rate, which we'll call 8%.” Graham assumes the founder starts young (this is Paul Graham, after all), so he runs the simulation for sixty years.

But together, these assumptions compound in profound ways. If you play out Graham’s scenario without a wealth tax, his hypothetical founder will be worth $10.3 billion at the end of their life. That’s good enough to be the 48th richest person in the United States in 2020—and exactly as rich as Gordon Moore, the 91-year-old founder of Intel, one of the most successful tech companies of all time. It’s several spots higher than WhatsApp founder Jan Koum, who owned an estimated 45 percent of his company (an astronomically high share) when it was acquired by Facebook for $22 billion in the eighth largest tech acquisition ever.

These are outcomes on the absolute edges of what a startup founder can achieve. To present them as somehow typical—and the tax implications as being of any consequence to most founders—is deeply misleading.

Ironically, Graham falls victim to the exact problem he warns about, and that Silicon Valley is supposed to be good at: Exponential growth is extraordinarily sensitive to seemingly insignificant changes. Graham makes three aggressive, though plausible, assumptions that, when compounded over many years and combined with the volatile growth dynamics of a startup, lead to a wildly implausible conclusion.

Long time horizons

Graham assumes that his startup founder lives for sixty years after accumulating $2 million in wealth. In the United States, at what age are people expected to live sixty more years? 18. Even if Graham’s founder lives ten years longer than average, that requires them to be worth $2 million at age 28, two years younger than the average YC founder. Given Graham’s skepticism of older founders, even that age is unrepresentative: Researchers found that the average age of successful founders is actually 45. For those founders, wealth would likely accumulate for thirty to forty years, not sixty.

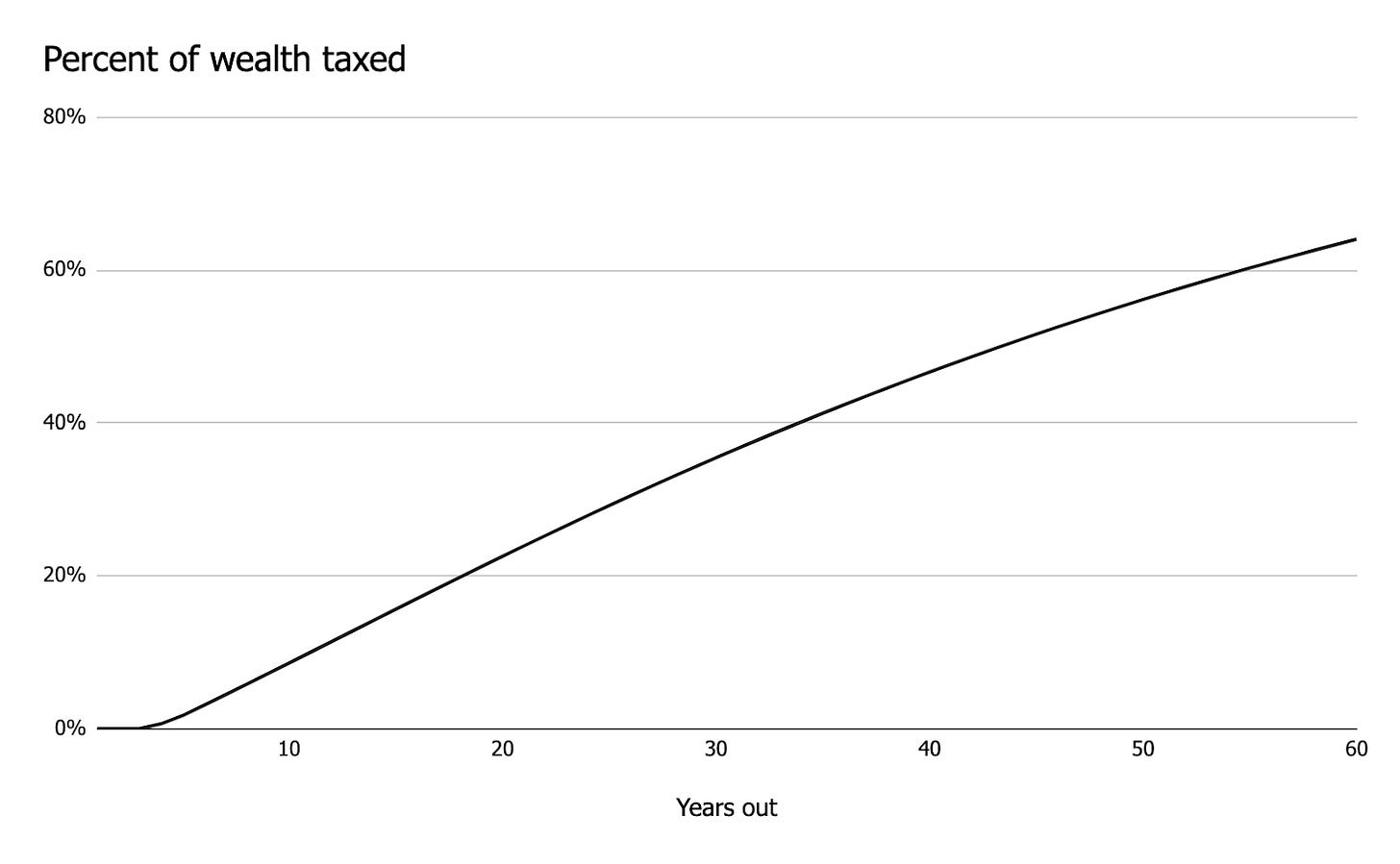

These shorter time horizons give wealth taxes less time to accumulate. Leaving all of Graham’s other assumptions in place (including the assumption that tax policy remains unchanged for decades), Warren’s tax plan would reduce a founder’s wealth by 23 percent over twenty years, 37 percent over thirty years, 48 percent over forty years, and 57 percent over fifty years.

Front-loaded growth rates

Graham assumes that a lot of growth comes early in his startup’s life. Rather than growing steadily, the value of his founder’s shares triple for two consecutive years, double for two years, grow by 50 percent for two years, and then grow at 8 percent a year for the next 54 years. These initial growth rates mirror the “triple, triple, double, double, double” rule of thumb that venture capitalists use to benchmark startups. Under this rule, startups hoping to be worth at least $1 billion should, after reaching $1 million in revenue, aim to triple revenue for each of the next two years and double revenue for each of the following three years.

Though startups do grow faster early in their lives, this rule isn’t particularly realistic. Great companies can be built over a slower, steadier pace. Shopify, the largest tech company founded after 2005, never tripled its revenue once, much less twice. (It’s worth noting that Graham is talking about valuation growth rates, not revenue growth rates, so they aren’t directly comparable. However, early-stage founders lose a good portion of their equity to dilution. For Graham’s founder’s wealth to grow at his assumed rate, the company’s valuation would have to rise even faster.)

These initial growth rates front-load the founder’s wealth accumulation. This pushes them over the taxable threshold quickly and, more meaningfully, ensures that their wealth tax bill compounds over a longer period of time. Slower initial growth, even if perfectly offset by terminal growth faster than 8 percent, has a significant impact on the final tax burden.

This effect is particularly visible on the extremes. Under Graham’s growth scenario, a founder loses 64 percent of their wealth. If, instead, the startup grew steadily by 15 percent a year for sixty years, they would pay out 46 percent over the same period. On the other extreme, if all the growth came in year one—essentially, if the founder’s wealth was inherited—they would be taxed a total 70 percent of their wealth.

Rapid growth rates

If one share of Graham’s startup was worth $1 at the beginning of his simulation, that same share would be worth $1,108 after forty years. If you bought $1 of Apple stock forty years ago in 1981, those shares would be worth about $1,200 today.

In other words, Graham’s startup is growing at the same rate as Apple—the most valuable company in the world and not exactly a typical “successful startup.”

More reasonable growth rates make Warren’s wealth tax much less onerous. Reducing growth rates by about a third would still put the founder on track to be a billionaire in today’s tax environment, but lower the burden of a wealth tax from 64 percent to 52 percent. For founders who only achieve the “modest” wealth of $100 million, which would put them in the richest few thousand households in the country, their tax burden would be 11 percent—a tax bill, by the way, that would be paid over the course of sixty years.

A more realistic scenario would temper all three dimensions: The founder’s wealth would grow more slowly, more evenly, and over a shorter period of time. Just as these assumptions compound up, they also compound down.

Across these scenarios, a founder could accumulate over $100 million in assets while paying an effective wealth tax rate as low as 5 percent and as high as 56 percent. And ultimately, that’s the point: In a long-running exponential models like this, fiddling with a few assumptions can change the headline from “Founders to lose two-thirds of wealth to Warren’s tax plan” to “Founders worth $100 million barely affected by proposed wealth tax.” With such a range of possibilities available, anyone with an Excel spreadsheet can easily craft a story to fit their narrative.

Consider, then, a final narrative: None of this math matters. These simple models are just a Rorschach test for pre-existing policy preferences. Graham’s calculations don’t tell us the hard truth about a wealth tax; they tell us Graham is opposed to a wealth tax, and he wants you to be opposed to it too. And anyone else who crunches a few numbers in a spreadsheet is doing the same thing.

Fair enough—I can use Excel too, and I see the ink blot differently. Here’s my headline: 230 years.

If we accept Graham’s growth model, his hypothetical founder is worth $3.7 billion after applying Warren’s wealth tax. Suppose that founder passes their wealth to their children, who decide to do absolutely nothing with their money. They invest in nothing but a can under their mattress. They earn no return on it. They produce nothing with it, other than an annual 2 percent wealth tax bill.

This person would be a billionaire for 64 more years. They would be worth over $100 million for 178 more years. By Graham’s own math, even with Warren’s wealth tax, a founder who puts in six years of work—the six years they earn above-market growth rates—will be worth more than $100 million for 230 years.

Either being worth $100 million for seven generations isn’t enough to “motivate founders,” or that number is bogus—and so is Graham’s 65 percent. Or maybe, Paul Graham is right: money really isn’t the main goal. And if that’s the case, in a country that needs to “attack poverty, and if necessary damage wealth in the process,” why stop at 2 percent?