A year from now, someone will write a great story about the class of 2021's college application essays. Not the good essays, but those written by white kids from northern Virginia and suburban Nashville and the entire state of Connecticut who try to fit a hand-me-down BMW, an annual family trip to Bermuda, and their intermittent participation in their church’s Adopt-a-Highway program into an answer to "How has overcoming adversity defined who you are today?"

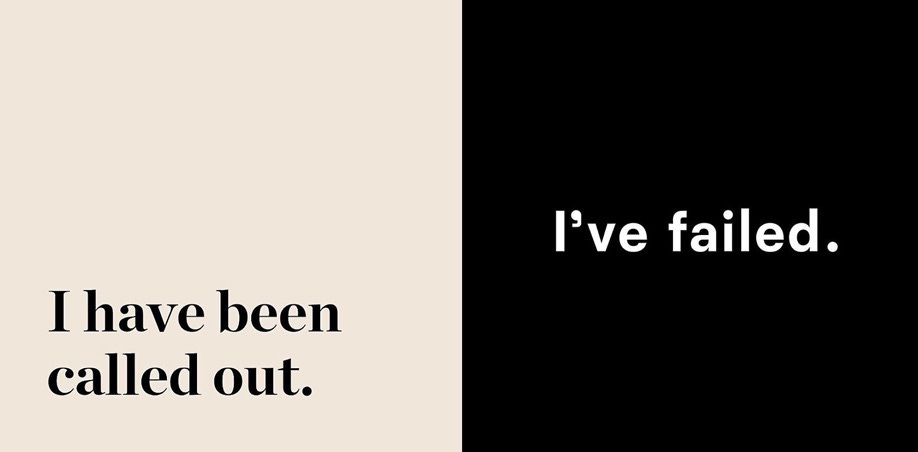

In normal years, these essays are terrible. (I know because I wrote several of them, all of which have been mercifully lost to the corrupted hard drive of a Gateway 2000.) This year, they'll surely be much worse. If the white adults of 2020 are any indication, the white college applicants of 2020 will replace their strained stories of disadvantage with eager claims of privilege, pronouncing themselves awake, remorseful, and reformed. I have been called out, they’ll say. WE ARE THE PROBLEM. i’m sorry please forgive me. I’ve failed. WE DID NOT SPEAK UP. Given how poorly PR professionals navigated these attempts at asking for credit by taking the blame, I feel for (and want to hear from) the college admissions officers who have to slog through thousands of teenage versions.

This genre of self-flagellations and confessions, though often unhelpful and sometimes offensive, emerged as one of the ways white people responded to last summer’s protests. For better or for worse, this, I thought, was the new normal.

Until it wasn’t. Last week, we found ourselves taking another trip around this awful merry-go-round of racial violence when a white man murdered eight people, six of whom were Asian women, in Atlanta. People quickly responded in ways similar to last summer: standing with Asian communities, organizing marches and protests, and compelling people to educate themselves that these murders are just a sharp edge to a long history of anti-Asian racism in the United States.

But, so far at least, the apologies are missing. I haven’t seen any statements taking blame for “not doing enough” to stop what happened in Atlanta or the underlying disease that caused it. If anything, the posts in my feeds (which obviously represent a sliver of what’s being said, and perhaps a very unrepresentative one) that address who’s at fault suggest the opposite, demanding that “we” hold “people” who stay silent accountable.

I don’t know what to make of this difference. Superficially, it seems like a positive change—the world doesn’t need Anthropologie to chase Instagram likes with tone-deaf virtue signaling in serif fonts tastefully off-centered over a millennial pink square. But I’m skeptical that these posts disappeared because we’ve collectively matured beyond them. When it comes to anything to do with race, America hasn’t earned the benefit of the doubt.

One possible explanation is just time. The current moment is still raw, and people haven’t had time to manufacture their contrition just yet. In time, it might show up.

But that seems incomplete, especially when you consider how permissible explicit anti-Asian racism still is. It’s hard to imagine that the United States has any sort of grasp on the systemic underpinnings of the murders in Atlanta when mainstream news outlets still frequently trade in Asian tropes.

Perhaps, then, people are reluctant to apologize for anything because there’s no systemic shield for them to hide behind. To declare yourself as part of the problem vis-à-vis anti-Black racism in America is—or at least can be framed as—declaring yourself as unwittingly complicit in a system bigger than yourself. You can admit to a crime without admitting to a specific crime.

If people don’t yet recognize anti-Asian racism as being structural, those who apologize for it have no cover. Those who admit guilt have to say what they’re guilty of. Vague confessions of weakness and inaction won’t do. So people point fingers (often at other non-white groups), at least until taking blame is rewarded with a pat on the head.

It’s a hell of a trick, and revealing of how potent America’s racial caste system is. It can hide in the shadows of unfulfilled promises of equal protection, and the moment those at the top acknowledge its existence—which Biden did in historic fashion during his inaugural address—many of them collectively and dramatically stand up like an inverted Spartacus, protecting, even if inadvertently, the embedded rot in the system.

In trying to understand the different reactions between the murders in Atlanta and the murders last summer, perhaps that’s the lesson: The only constant is the outcome. Racism in America isn’t defined by an ordered set of principles, but is shapeshifting and infinitely flexible, able to take whatever form is necessary to perpetuate it. Its apparent inconsistencies don’t undermine it, but make it stronger. You cannot take it apart with reason. You cannot pound the shape out of water.

Race and caste are not logic. They're an ugly, violent lie. And like any lie, it’s not held together by anything more coherent than the tangled web we weave to protect it.