9-9-6-0

When all you build is character.

“The future is already here,” the lede goes, “it’s just not evenly distributed.”

Similarly: The AI bubble will burst—it’s just that the disappointment won’t be evenly distributed.

First, I suppose—is AI a bubble? Some people are worried.1 Ben Thompson says yes, obviously: “How else to describe a single company—OpenAI—making $1.4 trillion worth of deals (and counting!) with an extremely impressive but commensurately tiny $13 billion of reported revenue?” Others are more optimistic: “While [Byron Deeter, a partner at Bessemer Venture Partners,] acknowledges that valuations are high today, he sees them as largely justified by AI firms’ underlying fundamentals and revenue potential.”

Goldman Sachs ran the numbers: AI companies are probably overvalued. According to some “simple arithmetic,” the valuation of AI-related companies is “approaching the upper limits of plausible economy-wide benefits.” They estimate that the discounted present value of all future AI revenue to be between $5 to $19 trillion, and that the “value of companies directly involved in or adjacent to the AI boom has risen by over $19 trillion.” So: The stock market might be priced exactly as it should be. Or it could be overvalued by $14 trillion.

Either way, though—these are aggregate numbers; this is how much money every future AI company might make, compared to how much every existing AI company is worth. Even if the market is in balance, there are surely individual imbalances. Sequoia’s Brian Halligan: “There’s more sizzle than steak about some gen-AI startups.” Or: “OpenAI needs to raise at least $207 billion by 2030 so that it can continue to lose money, HSBC estimates.” Or: “Even if the technology comes through, not everybody can win here. It’s a crowded field. There will be winners and losers.” That is the nature of a gold rush, though, even when there is a lot of gold in the ground. Some people get rich, and some people just get dirty.

No matter, says Marc Andreessen; this gold will save the world. And the people digging for it are heroes:

Today, growing legions of engineers – many of whom are young and may have had grandparents or even great-grandparents involved in the creation of the ideas behind AI – are working to make AI a reality, against a wall of fear-mongering and doomerism that is attempting to paint them as reckless villains. I do not believe they are reckless or villains. They are heroes, every one. My firm and I are thrilled to back as many of them as we can, and we will stand alongside them and their work 100%.

I do not know if the tech employees are heroes, but they are working hard. Some, monstrously so:

recently i started telling candidates right in the first interview that greptile offers no work-life-balance, typical workdays start at 9am and end at 11pm, often later, and we work saturdays, sometimes also sundays. i emphasize the environment is high stress, and there is no tolerance for poor work.2

This is the new vibe in Silicon Valley: Grinding, loudly. Hard tech, and extremely hard core. Because that’s what’s needed to meet the “deranged pace” of this historical moment. Venture capitalist Harry Stebbings: “7 days a week is the required velocity to win right now.” Cognition’s Scott Wu: “We truly believe the level of intensity this moment demands from us is unprecedented.” From others—this isn’t mere capitalism; this is a crucible: “‘This work culture is not unprecedented when you consider the stringent work cultures of the Manhattan Project and NASA’s missions,” said [Cyril Gorlla, cofounder and CEO of an AI startup]. ‘We’re solving problems of a similar if not more important magnitude.’”

So far, so good, at least for the capitalists: According to CNBC, there are now 498 private AI companies worth more than $1 billion. A hundred of them are less than three years old. There are 1,300 startups worth more than $100 million. And these companies have created dozens of new billionaires.

In recent years, this has become the math that punches Silicon Valley’s clock: 996—work from 9 am to 9 pm, six days a week. Seventy-two hours a week; 3,600 hours a year; 10,000 hours in three years. But if that adds up to a billion-dollar payday? Or even a pedestrian few million? Just hang on. “‘I tell employees that this is temporary, that this is the beginning of an exponential curve,’ said Gorlla. ‘They believe that this is going to grow 10x, 50x, maybe even 100x.’” Another founder told Jasmine Sun their plan—get in, get rich, get out:

I asked a founder I know if he thinks that AI is a bubble. “Yes, and it’s just a question of timelines,” he said. Six months is median, a year for the naive. Most AI startups are all tweets and no product—optimizing only for the next demo video. The frontier labs will survive but it’ll be carnage for the rest. And then what will his founder friends do? I ask. He shrugs. “Everyone’s just trying to get their money and get out.”

A few years of hard work, funded by borrowed money. And what’s just a few years?

There is a point during every party, when the alcohol takes hold and the music swallows you whole, that you lose yourself in the fever. The moment, indomitable. The walls, impenetrable. But how quickly a night can turn. How quickly a tune can change.

Back in my day, it was banking and consulting: “Among men who are entering the workforce next year, 58 percent are taking jobs in the finance and consulting industries. Among Harvard women in the workforce, only 43 percent are going into finance and consulting.” In 2011, in her canonical investigation of this phenomenon, Yale senior Marina Keegan interviewed her classmates to figure out why so many of them took jobs they didn’t seem to really want. Their answer? This is temporary:

Annie Shi ’12 has similar justifications for her job at J.P. Morgan next year. When asked what she might be most interested in doing with her life, she mentioned a fantasy of opening a restaurant that supports local artists and sustainable food. Eventually, she’s “aiming for something that does more good than just enriching [her]self.” She just doesn’t think she’s ready for anything like that quite yet. …

“I’m practical,” she says. “I’m not going to work at a non-profit for my entire life; I know that’s not possible. I’m realistic about the things that I need for a lifestyle that I’ve become accustomed to.” Though she admits she’s at least partially worried of ending up at the bank “longer than [she] sees [her]self there now,” at present she sees it as a “hugely stimulating and educational” way to spend the next few years.

A few years of hard work, as an investment into the rest of your life. And what’s just a few years?

In a tragic twist that many of you probably know: Nine months after publishing her story, and five days after she graduated, Marina Keegan died in a car crash.

But there’s another twist, that you may not know. Here’s a second quote from Keegan’s article, from a different classmate who was almost seduced by a pitch from McKinsey: “There’s definitely a compulsion element to it. You feel like so many people are doing it and talking about it all the time like it’s interesting, so you start to wonder if maybe it really is.” That classmate was Tatiana Schlossberg.

You can live your life on borrowed money, but there is no such thing as borrowed time.

What happens if—when?—the AI bubble bursts? We’re frequently told the stakes. In the United States, “AI is the only source of investment right now,” some economists say; without it—without huge companies like Amazon and Alphabet spending billions to build huge factories for their huge computers—it’s “plausible that the economy would already be in a recession.”3 Other economists: “This A.I. gold rush is generating all the excitement and papering over a drift in the rest of the economy.”

In San Francisco, there would be smaller, quieter consequences. Companies will pivot themselves in circles; evaporate; sell themselves for parts. There will be thousands of employees, grinding for the 10x, 50x, maybe even 100x payday, collecting nothing. There will be abandoned options, vested through years of hard work, unexercised and returned. Sometimes, 996 adds up to generational wealth. Sometimes, it adds up to zero.

That is at least one big difference between a party and a bubble: A hangover comes with memories.4 The night out was the point; the morning after is a delayed invoice. An eye for an eye.

But a collapsed company is a price paid for nothing. It is the entire transaction. It is a hangover, for a party that never happens. It is a discarded lottery ticket, scratched for 72 hours a week, for years. Sometimes, there is just borrowed money, and lost time.

When you join a startup, they don’t tell you about this part. They tell you about the potential. They paint their vivid visions5 in pitch decks. They sell the better world they’re building to their employees. They give you worksheets: Your equity, if we sell at our last valuation; if we IPO; if we become Salesforce.

Somewhere at the bottom, they put the disclaimers. Startups are inherently risky. Your options may have no financial value. “You should consult with your own tax advisor concerning the tax risks associated with accepting an option to purchase the Company’s common stock.” Everyone knows this, of course.

But, zero? We aren’t conditioned to understand that, not really. Hard work feels like it must have some reward; unpleasant experiences must be building something. We grow up with a sense of cosmic balance: Our parents are watching; our teachers are watching; God is watching; Santa is watching. Surely, the same saviors must exist here. Even if the market turns, an acquirer will save you. Your boss will take care of you. Your investors will help you out. Everyone knows they may not win the lottery. But all the work—to build a resume, to get a job, to help create a company—surely, it must be worth something? It’s hard to imagine otherwise, because nobody paints a vivid vision of that future.

Or at least, startups don’t—but they’re out there:

Fred sits alone at his desk in the dark

There’s an awkward young shadow that waits in the hall

He’s cleared all his things and he’s put them in boxes

Things that remind him, life has been good.

25 years, he’s worked at the paper

A man’s here to take him downstairs

“And I’m sorry, Mr. Jones, it’s time.”There was no party, there were no songs

‘Cause today’s just a day like the day that he started

No one is left here that knows his first name

And life barrels on like a runaway train

Where the passengers change

They don’t change anything

You get off; someone else can get on

“And I’m sorry, Mr. Jones, it’s time.”

…

He’s forgotten but not yet gone.

Of course, these aren’t real tragedies. Writing off your options after working a good job in a comfortable chair—even for 12 hours a day—is not a terminal diagnosis; it is not even bad. Most of us will, at worst, be passing extras in someone else’s tragedy; we are unlikely to be its main character. This week, of all weeks, we should be grateful for that, and for the good twists in many of our stories.6 So many of us have won so many lotteries already.7

And it must also be said: Silicon Valley produces plenty of circular slop. Legions of startups exist because they are lottery tickets, and legions more exist to sell stuff to them. Is it a tragedy that they are gone? A comedy? A blessing?

Still. That is too crude. Wherever you work, do you know good people, working hard? Have you invested in people, and asked to take their time in exchange for your lent money? Do you know people putting in honest hours for a fraction of the benefits of their boss? Do you know people who are giving their time—so much of it, time that cannot be returned—to the office? Would you be sad for them—mad for them—if it does not turn out?

More calculus that we all have to do:

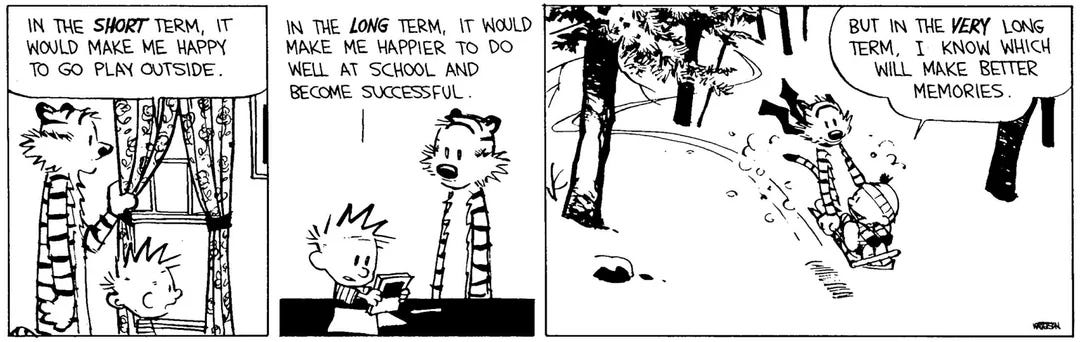

We imagine ourselves as Calvin: Do we do what makes us happy now? Do we invest in our future? Do we eat the marshmallow today, or wait for more later? Do we make memories with our friends?

But we forget: The punchline of the strip doesn’t work without Hobbes. Calvin’s memories—our memories—only matter when Hobbes is there. And, of course, the corollary: Hobbes’ memories require us.

If you work here, in technology, you know an entire Rolodex of people, doing their homework, for the long term. You might want the best for some of them; some of them might be your friends. For many of them, it won’t work out. “Not everybody can win here. It’s a crowded field. There will be winners and losers.”

That part—their disappointment; yours; somebody’s—is inevitable. Though it can’t be stopped, and their time cannot returned, that doesn’t mean nothing can be done. Because in the very long term, as Calvin says, the memories matter than the success.

But their memories require us. So, before it is too late: Be Hobbes. Pay attention. Watch your friends work; see what they are sacrificing. Call them; email them; wish them a happy birthday, even if you cannot tell them directly. See, and show them that you see.

Because when a bubble bursts, and people’s work gets erased and their hours wasted, all that remains is what other people witnessed. And it is on each of us remember what they hope we do not forget.

Typically, investment firms make money by charging a small management fee, and by taking a larger cut of their investments’ earnings. And typically, these fees are about 2 percent and 20 percent. So, if you gave (a hypothetical) benn.ventures $100 to invest, I’d take $2 as a management fee, and invest the remaining $98 in various startups. If those investments return $100 on top of the invested capital, I’d give you your initial $98 dollars back, plus $80 of the returns, and I’d keep the other $20. The point of this structure is to guarantee that I make a little bit of money for my efforts—the 2 percent fee—while still incentivizing me to make as much money as possible with the investments.

But if you’re a celebrity investor, this might not be an optimal model. First, a lot more people might want your investing opinions than are able to give you money. Only charging your investors a management fee is leaving money on the table. Second, if people are paying attention to those opinions, they can become somewhat self-fulfilling. (When Warren Buffet says he likes a stock, the stock goes up.) And third, if you’re a celebrity investor, you probably want to be a celebrity, and want attention as much as money.

A better model, then, might be to publish your opinions, charge people to read them, and then charge a much smaller management fee. You could make more guaranteed money, pump your positions, offer more compelling terms to prospective investors, and get even more attention, all at once.

Anyway, earlier this year, celebrity investor Michael Burry managed a $155 million fund, which would bring in about $3 million in management fees. He closed that fund, and now puts all of his investment advice on Substack, behind a paywall that costs $40 a month. He has about 100,000 subscribers. If ten percent of them pay, he’ll make $400,000 a month, or about $5 million a year. That’s better! And here we are, talking about him!

Regarding the horrific casing, [sic].

This Black Friday, I hope I can trust all of you to do what’s right for our country.

For example, after working at J.P. Morgan for three years, Annie Shi ‘12 opened a very good restaurant.

I think about reincarnation sometimes. If you were a disembodied soul, and didn’t know which organism you’d be placed into, how would you feel about your current draw? First, you would have to be born as a person, and not a termite or a fern or slaughterhouse chicken (though you were not born a house cat, which seems pretty solid). Second, you’d have to be born in an equally privileged and broadly painless historical era (i.e., not the Stone Age or in a time before anesthesiology). Third, you’d have to be born into greater relative social wealth, or granted more physical or mental gifts. For most people here, those aren’t good odds! You could be reincarnated thousands of times, and this is still probably the best shot you’ve got!

This a great take. Thanks for the read!

Love this!