Enough

The math in the headlines.

At a party given by a billionaire on Shelter Island, Kurt Vonnegut informs his pal, Joseph Heller, that their host, a hedge fund manager, had made more money in a single day than Heller had earned from his wildly popular novel Catch-22 over its whole history. Heller responds, “Yes, but I have something he will never have … enough.”

– from Morgan Housel’s The Psychology of Money, recounting a story from Vanguard founder John Bogle

It’s both everywhere and, somehow, still, nobody knows how to talk about it.

I don’t know what else we would say. I don’t know what we can say, other than what everyone already says: “It’s gotten so crazy,” and, “can you imagine?,” and, “man, that is a lot of money.”

But man, that is a lot of money.

Which one? I can’t keep track. It’s OpenAI, raising money that values the company at $500 billion, which is $200 billion more than its valuation just five months ago—which was, then, the largest private fundraise in history. It’s Meta, adding almost $200 billion to its market cap in a day, only to be outdone by Microsoft going up by $265 billion on the same day. It’s Microsoft, becoming a $4 trillion company, less than seven years after Apple became the first company to reach a measly one trillion. (Even Broadcom—whose website looks like a regional home security provider1—is worth more than that today.) And that all happened over the last week.

The week before, it was Ramp, raising $500 million—million, with an M, how quaint—at a $22.5 billion valuation, less than two months after they raised $200 million at a $16 billion valuation. It was Meta, buying Scale AI’s CEO for $15 billion, or OpenAI, buying Jony Ive for $6 billion. It was Meta again, trying to buy an engineer from Thinking Machines for $250 million a year, and not only getting rejected, but getting rejected for economically rational reasons, because Thinking Machines is currently worth $12 billion, and their executives’ pay packages might already be worth more than Meta’s offers.2 It’s $200 million to poach an Apple executive, and stories about $18 million offers, getting relegated to the final line of a daily beat report.

You become numb to it, until some fresh blockbuster jars you loose again. In one day, Microsoft grew by more than all of Roche ($247 billion), Toyota ($237 billion), IBM ($233 billion), and just a couple AI engineers less than LVMH ($266 billion). In one day, Mark Zuckerberg’s net worth grew by $27 billion—a full Rupert Murdoch; a full Peter Thiel; a full Steve Cohen; a full Jerry Jones and a full Marc Benioff. In a recent column about the OpenAI fundraise, Matt Levine reminded us that 1 basis point of OpenAI—one-hundredth of one percent; 0.01 percent; the amount an average employee gets when they join an average late-stage startup—is worth $50 million.

Those are the numbers now, but I don’t know what to do with any of them.

I met Steve Ballmer once. Ballmer is worth about $145 billion—the tenth richest person in the world, though not even half as rich as Elon Musk. In America, the average person is worth about $415,000 (crudely, the average household is worth $1.06 million and has 2.55 people in it). We encounter about 40 people a day; 40 people times $415,000 is a total cumulative wealth of $16.6 million. So, the face of $145 billion is either Steve Ballmer, or every face we see for just under 24 years.

Or, put differently, if you were the world’s most cunning and complete thief, and you could steal everything from someone the moment you saw them—their wallets, their watches, their bank accounts, their houses, their 401k’s, their life insurance policies, all of it, in an instant, just by passing them by—it’d take you 24 years to steal as much as money as Steve Ballmer already has.

I don’t know what to do with that either.

I do know one thing though: Never do the math.

I met Steve Ballmer because Microsoft was buying the Yammer, the startup where I worked.3 I was employee #250, hired three months before the acquisition.4 My Yammer shares—about a third of a basis point of the company; 0.003 percent; had we been bought for OpenAI’s current valuation, it would’ve been worth $17 million—was converted into Microsoft equity. All told, from vested options, on-hire bonuses, and employee stock ownership grants, I ended up with about 1,000 shares. I sold them all in 2012, when Microsoft hit a 10-year high—$32 a share. I celebrated by buying a big Lego.

Never do the math. Microsoft now trades at $520 a share. My shares, long sold for a fraction of that, would now be worth a half a million dollars.5

Never do the math. Which shares did you sell? Which job did you not take; which recruiting email did you not respond to? When did you get your first email about bitcoin? This was mine:

On 20 May 2014:

I have a few Bitcoin-related ideas.

Richard

Bitcoin—trading today at $117,000—was $494 back then, about the same price as my Lego. If I had bought bitcoin instead of a toy, it’d be up 24,000 percent, to $100,000. If I had quit my job and become a crypto day trader, I’d be liquidating my nine-figure Coinbase account and retiring, like one of my old Yammer coworkers recently did.

We’re not supposed to do the math, but we do, sometimes.

Of course, we could also do the math in the other direction. Tech is the richest industry in the world at the richest time in history. How unlucky, perhaps, to not buy bitcoin in 2014—but how obscenely lucky, undoubtedly, to be given everything else. Why do we never do that math?

In Silicon Valley, money was often treated like a footnote. It’s the aside; the afterthought; the unintended byproduct of making the world a better place. It was a perk, like having an office stocked with snacks and beer. Ask a founder what made them start their company, and they’ll say they’ve always known that they’re a builder. They’ll talk about wanting to make something fully their own. They’ll talk about reinventing healthcare for their dying uncle, or developing the next generation of personal computers, or manufacturing low-cost sheet metal in autonomous factories, because western democracy depends on it.

Ask someone at an AI lab why they work there, and they’ll talk about the team, the energy, the scale of the problem. They’ll talk about the cause: AGI; safe AGI; American AGI.

Ask a VC why they’re in venture capital, and they’ll talk about how interesting the job is. They’ll talk about how many great people they get to work with; about how much autonomy they get; about how they’re lucky to get to think about so many different things.

“And, you know, the money isn’t bad either,” they all toss in at the end. As a footnote.

But even during the prior boom years, the footnotes were already beginning to overtake the main text. They were quietly becoming the main attraction. You’d go to dinners and meet people—founders, VCs, employees of big companies whose tenures predated your awareness of the company—and you could see it: Everyone starting to poke around the edges of the math. “At least my bank account liked it,” an early employee once said of his experience at Slack. “Yeah, I mean, we did alright,” a founder told me a few weeks after selling his startup to a large public company. “Look, the fund’s had a good year,” a VC told a table at a conference dinner.

There are never numbers—numbers are gauche; most everyone is very lucky here;6 and we’re not private equity raiders, but TeChNoLoGiStS—but then, everyone eventually goes home and does the math.

Sometimes you catch it, in the moment. Sitting behind someone at a conference last year, while a notable CEO chatted fireside with a VC, I watched over their shoulder, a voyeur to their voyeurism:

Google: [ The CEO’s company ] crunchbase

Google: [ The CEO’s company ] valuation

Calculator: [ The valuation ] * .25

Calculator: [ The valuation ] * .15

Google: [ The CEO ] net worth

iMessage: watching [ the CEO ] talk, pretty sure he’s a billionaire

Google knows; it sees our curiosity. Go ahead, search for that hyped startup’s CEO. Type their full name in Google; see what it suggests next. Age. Wife.7 Net worth. We put on our bios that we’re builders; we put in our mission statements that we’re here to build great things; we put in our manifestos that our fund exists to support founders who are building for humanity. But there are other things we care about that we only tell Google. Because how is the hedge fund manager supposed to know if she has enough if she doesn’t know how much other people have?

And that was then, when all the numbers were still private whispers, and not published in Reuters. That was then, when a big windfall could buy you a house, and only the chief people officer of Microsoft could buy a WNBA franchise with 25 years of accumulated equity. What do we Google now, when a 25-year old engineer can buy a team, with their salary. Dizzying wealth is no longer just in the corner office of the top floor; it’s now down the hall, at the desk next to you. It’s in your coworker’s offer letter, because they joined six months before you did; because they were in the same grad program as the founder; because they got leveled higher by their hiring manager. You don’t look around the office and wonder, sometimes? You’ve never done that math? Sure, we’re building for humanity, but we’re only human.

Mark Zuckerberg, on his spending spree:

Advances in technology have steadily freed much of humanity to focus less on subsistence and more on the pursuits we choose. At each step, people have used our newfound productivity to achieve more than was previously possible, pushing the frontiers of science and health, as well as spending more time on creativity, culture, relationships, and enjoying life.

The utopian promise of AI is a world of infinite abundance. We all live materially rich lives, on the dole of our loving machines, satisfied and fulfilled.

Maybe, AI solves world hunger and famine; maybe it cures diseases and ends wars. Maybe it can relieve the terrible toll of acute suffering. The rest of the calculus barely matters, if that’s on one side of the equation.

But what of this hypothetical AI’s less profound gifts? Will the stuff it gives us make us happier? More satisfied? I don’t know. Fulfillment, it seems, is comparative. The math nags us, because it tells us what a different version of us might have. We don’t do the math to measure ourselves; we do the math to compare ourselves.8 And if Zuckerberg is right—if we have a few machines that make and do everything—the current concentration of AI money may be the prologue to how big the numbers could get.

A final irony, perhaps: Is the promise of AGI and universal abundance incompatible with social media? No matter how much that machine makes for us, will we ever be satisfied if we can’t stop ourselves from doing the comparisons? If we all stare into a global feed of what the richest among us have, will we ever stop doing the math? If we build a machine that can give us everything, when do we dismantle the machine that makes us doubt that it is enough?

Look at that grainy logo! That Tron brain! Those menus when you click on “Products” and “Solutions”! If nothing else, you know that website wasn’t vibe-coded.

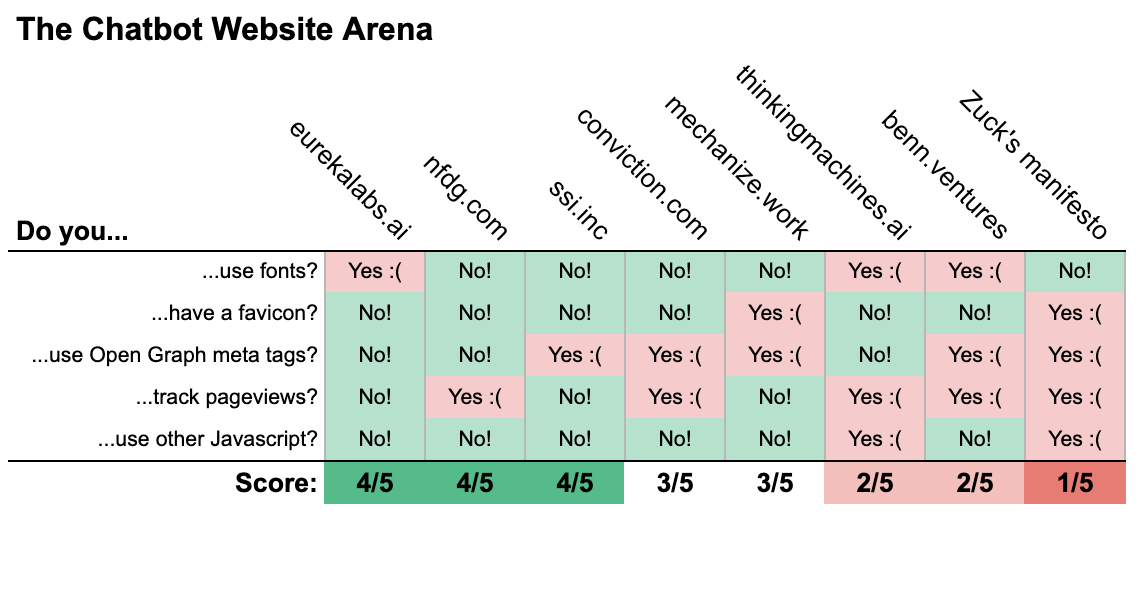

The real reason Zuck is struggling to hire these people is because his website is bad. It’s got stock fonts, sure, but pageview tracking? 57,000 characters of Javascript? A favicon? No serious AI lab would ever.

He showed up at the Yammer office with some other Microsoft executives, on the day they announced that they were acquiring us. The presentation was in our cafeteria, and the lunch tables had been pushed back to make room for the stage. As someone else from Microsoft talked about how “excited they were for this new partnership,” Ballmer sat on one of the tables, cross-legged, rocking back and forth, ready to combust. He spoke briefly at the end, and said we were all getting custom Xboxes. A few months later, we got the Xboxes—and were told that they took a while, because he had made that part up on the spot.

Fun fact: We learned about acquisition—which first became a story because a reporter overheard people talking about it at a coffee shop—on the same day that my team went to this Giants game. It’s hard to say which was a more important event in my life.

My Lego, long unboxed, is up nearly 400 percent. Never do the math.

This is important part of the performance, I think. Almost everyone who works around startups and the tech industry is aware of their absolute luck, and the polite thing to do is to say that, and move on. Moreover, the inner anxieties of the bourgeoisie is not a morally pressing question. But it is perhaps an interesting question, because, one, society is increasingly bent around those people’s feelings, and two, given that profound luck, why are we anxious at all?

The recent grad is troubled by how much the designer who got the job they want makes; the designer is troubled by how much the engineer makes; the engineer by the researcher; the researcher by the founder that got acquired; the acquired founder by founder who acquired them; the founder by the billionaire; the billionaire by Jeff Bezos; Jeff Bezos by Elon Musk; and Elon Musk by the recent grad.

Right there with you. The company that I was a small part of was sold to Microsoft in 1999, just before the .com bust and our options didn't transfer until after the stock had plummeted. Stayed there for the next 14 years, seeing little growth (but great roles, challenges and competitive salary)...just as I left, Satya was named CEO and share value started its rise. Sadly, I sold much of my stock to move east. Can't change it, would probably do it again...don't do the math!

in 2012 I bought approximately $650k (at today’s prices) worth of mushrooms for a friend