Don't be evil*

*Subject to change without notice. Terms and conditions may apply.

What was remarkable about the 2012 Gizmodo article titled “Google’s Broken Promise: The End of ‘Don’t Be Evil’” wasn’t the accusation that Google had done a bad thing; what was remarkable about it was that it too so long for Gizmodo to accuse Google of doing a bad thing.

Google was founded in 1998. It went public in 2004. In 2011, it employed 32,000 employees, brought in $37 billion in revenue, and made almost $10 billion in profit. By any reasonable measure, it was already the sort of enormous corporate behemoth that people generally assume is evil by default.1 But for Google, it took fourteen years of success and attention for “many to wonder if Google has gone bad.”2

There are two ways to think about this. The first is that Google was run by exceptionally good people. They were sitting at the controls of a staggeringly well-configured machine, and they had many evil dials in front of them that would make them even more money. For Google’s leadership team to avoid the temptation to turn those dials, they must’ve been remarkably benevolent, or at least anti-malevolent. Many companies sell their souls for far less than Google could’ve made by selling a few small pieces of theirs.

The second way to think about it is that Google was an exceptionally good product. The people who ran Google weren’t especially moral, and their ambitions to not be evil weren’t especially unique. A lot of people have idealistic visions to do things “the right way” when they start companies; they want to make useful products, to build genuine communities, to create good jobs for employees, to go high. Sure, the lofty promises to make the world a better pitch are cringe, but they’re usually bad sales pitches, not outright lies.

Still, a lot of companies end up going low, because building a company is hard. When a company is struggling—when the machine isn’t working, and its survival is hanging in the balance—the dial that does evil looks a lot more appealing. Evil, or at least compromises, starts to feel necessary, and how wrong is it to do what’s necessary? Google avoided that dial because it was making enough money to not need it. When you have a printing press in your basement, you have a lot of leeway in how you can run a company. You don’t need to cheat your users or the law; you don’t need to get in dirty scraps with competitors or the press; you don’t need to make pushy sales calls or entrap customers in subscriptions they can’t cancel. Deep down, Google probably had the same two values that every other company has: First, make money, and second, some other nice sounding stuff, in that order. Google was special because it did such a good enough job of making money that it was able to do the nice stuff too.

Other companies rarely have that luxury. They aren’t evil at birth, run by bad people, or fundamentally better or worse than Google was. But idealism has a price, and most companies can’t afford it.3

The same logic applies to other things. I don’t believe that most politicians are inherently greasy people. The lower levels of political office aren’t glamorous, powerful, or well-paid, and the many of the people who run for those offices are running with honest intentions. But politics is a dirty business, and darkness makes monsters of us all. In that view, the politicians that stay high aren’t the ones that are morally unimpeachable, or at least just morally unimpeachable; they are the ones who are gifted enough to stay high. As a politician, Barack Obama was a generational talent, and his presidential administration was “remarkably scandal-free”—and those two things are related.4

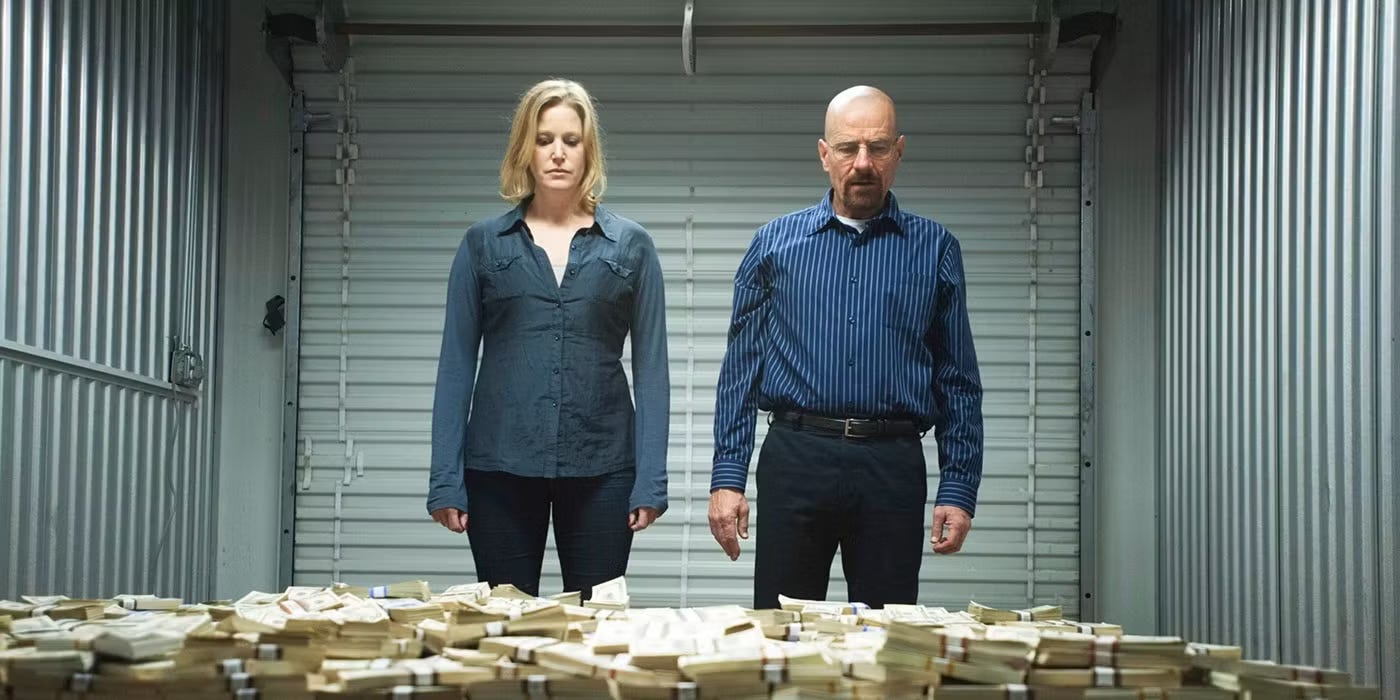

The point of all of this is that wanting to do something and being able to do it are not the same thing. When something breaks bad—a company, a politician, a dying high school chemistry teacher, an athlete on the margins of the league who decides to take steroids, a blogger who becomes a shameless hack for the likes—it’s easy to say that they should’ve known better. But they probably did know better. Their problem isn’t awareness or will power; their problem is a skill issue, and a system—the league, the market, the economy—that will devour anyone who isn’t elite.

Someone recently asked me why we sold Mode, a reluctant BI tool that’s core audience was technical data teams who wanted to write code, to ThoughtSpot, an unapologetic BI tool that sold to drag-and-drop enterprise business users. The question wasn’t so much about the decision to sell the business, but about the decision to sell it to a company that did such a seemingly different thing. If our original intention was to make something that let analysts work in the tools they wanted to use—in SQL, in Python, in an monospaced, dark-mode IDE—why did we agree to smash it together with a product that’s explicit goal was to replace all that stuff?

The answer, more or less, is that we weren’t elite enough at what we did. Our initial ambition was to build something specialized—an opinionated power tool; something “built for analysts;” a technical product that was comfortable telling people that you need to be at least this tall to ride this ride. And our first pitch decks laid out a product roadmap that was true to this ideal.

But our ability to keep to that promise was dependent on our ability to build a business around it. Though investors gave us money to make the next great tool for analysts, they really gave us money because they wanted us to eventually give them more money back. If every venture-backed company has two ordered values—make money, and some nice sounding stuff—they also have two unstated product values—build something that you can sell, and build the thing you want to sell. And you have to be good enough at the first one to do the second.

We weren’t quite there. Though we could sell Mode’s product well enough to survive, we couldn’t sell it well enough to be uncompromising on our earliest ideals. Analysts didn’t have big enough budgets; they were too hard to find and too expensive to sell to; they didn’t have enough organizational authority to make their CEO buy the technical tool they wanted over the drag-and-drop enterprise business intelligence tool that the finance team wanted. Perhaps we could’ve made different decisions about what we built or how we marketed and sold it, and we would’ve found our own printing press in the basement. Perhaps the market for the product we wanted to sell simply wasn’t that big. But regardless of the reason, the outcome was the same: The result didn’t match the ambition, and we didn’t earn the right to build something other than a BI tool. So we had to break the glass, and turn the evil dial.5

But there is one important caveat to all of this: Results aren’t measured on an absolute scale. If it takes a one-in-a-billion talent to survive running for president of the United States without breaking bad, then it takes a one-in-a-million talent to survive in the House of Representative, and a one-in-a-thousand talent to do it on the city council of a small town. Similarly, the ambitions that broke OpenAI’s will to be a non-profit were bigger and more crushing than the ambitions that broke Hashicorp’s commitment to its open source principles, which were bigger than the ambitions that pressured us into building a data tool that we could sell to people who weren’t just analysts. Though no company can choose its true values—there are always two, in the same order—they can choose the size of the first one, and, by extension, how much pressure it exerts over the second. In our case, there was a business of a different scale, chasing tens of millions of dollars in revenue rather than hundreds of millions, that could’ve outpaced its first value enough to to stay true to its second.

Anyway, yesterday, Sarah Guo, an investor and the founder of an AI-focused fund, said now is the time to chase the biggest ambition you can imagine:

If you're a founder, this is the moment you dream of. Technical paradigm shifts on this scale come rarely. When they do, they tend to birth a cohort of companies that define the decades that follow. Intel and Microsoft in the 70s and 80s, Cisco in the 80s and 90s, Amazon and Google in the 90s and 2000s, Facebook and Salesforce in the 2000s. And now Nvidia, the three-decade sleeper. Who will be the other giants that emerge from the AI explosion?

I suspect they will be the companies with a few characteristics: those pursuing the most ambitious visions, those experimenting at the frontier, inventing a new way of interacting with technology, and those companies who recognize what a special moment in time it is. …

So if you're working on something in AI right now, ask yourself - what's the most ambitious version of this? What will be possible next year? We see too many startups undershoot in their capability predictions. We hope to see more startups overshoot. …

Tectonic plates that have been slowly shifting are about to collide. Will you be in a position to ride out the quake and build something enduring in its aftermath? If there was ever a time to be maximally ambitious, it's right now.

On one hand, I get it. Venture capitalists’ make money when they bet on more big winners, not when they bet on fewer losers. And when you're in the thick of working at a startup, pep talks about your potential are nice. Microsoft! Amazon! Facebook! Nvidia! Steve Jobs! The man in the arena! Sometimes, you really do need to be reminded that you can build whatever you want, and aim however high you want.

On the other hand, aiming high—which, in Silicon Valley, is often easier to do accidentally than intentionally6—has strings attached. Some of those are well understood: Financial dilution; a gradual loss of corporate control; a board that might fire you; a long-term commitment.7 But one of the less visible strings is the one that recalibrates your own internal compass.

Because if you shoot for the stars and land on the moon, that’s great—but the thing that lands on the moon probably doesn’t look like the thing that was shooting for the stars. The open source company becomes one with an aggressive sales team and hated paywalls; the startup that wanted to get rid of management and performance reviews becomes a company with five different levels of senior engineer; the data tool that refuses to call itself a BI tool sells itself to a BI tool.

Don’t be evil,8 absolutely. But unless a company really is that singular generational giant that emerges from the AI explosion—unless it really are Google—it’s probably going to find itself walking awfully close to the line.

In 2012, Goldman Sachs was almost an identically-sized business—they made $34 billion in revenue, $7.5 billion in profit, and also employed 32,000 people—and people had been accusing Goldman of being a great vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity for years.

The great rhetorical styles: Aristotle, appeal to people’s sense of ethics, emotion, and logic; Socrates, invert the traditional roles of teacher and student to help people critically question new ideas; Donald Trump, say “many people are saying” until many people say it.

There is a spectrum of bad things a company can do, of course. If a company can’t survive without doing fraud, crimes, and outright unethical things, it shouldn’t exist at all. But a lot of startups want to hold themselves to higher standards than what is required by the law or a basic sense of moral decency. And if push comes to shove, most companies will sacrifice those values before they sacrifice their viability.

You don’t have to pitch many VCs to figure out what they respond to: Ambition, audacity, and very big numbers. Small ideas can get ratcheted up, especially in hot markets. There are surely countless AI projects that have become bold promises that their creators never intended to make.

Man, what a neg. This post is about 1,000 words on why you shouldn’t start a startup and why it’s hard, and then ends with, “But you’re not a wimp, are you?”

To be clear, “evil” is metaphorical, ish. By don’t be evil, I mean, have your ideals, which might be about the type of company you want to create, or the product you want to build, or your values, or how many days you want to work, or what type of swag you want to give people, or whatever. Not being Proper Evil should not be an ideal. Please don’t be Proper Evil.

A brilliant post! Captures much of what I think should be conveyed to young people thinking about their careers. Very well said.

Evergreen thinking. Thank you for not oversimplifying, the nuance is what makes this hard, yet public discussions simplify that and make it look easy. Nothing is easy about propositions that can feel like lose/lose without nuanced framing.