How to play Wordle

Using data from a quarter-million tweets to turn Wordle into a numbers game, and what it teaches us about the truth.

It all started with a fumble. On February 7, 2016, eight minutes into Super Bowl 50, Cam Newton, the face of the Panthers’ franchise and the dynamic future of a reinvented NFL, fumbled the ball on drop-back and inexplicably balked at recovering it. The Broncos, a team led by aging Nationwide salesman Peyton Manning, picked it up, ran it back for a touchdown, and ran away with the Super Bowl title.

Cam’s career fell apart with that fumble, and the rest of the world went with him. Colin Kaepernick was blackballed; Tom Brady kept winning. A tyrant took charge. The virus got out; the villains got acquitted. The deserts froze; the oceans caught on fire; the sky turned orange. The train came off the tracks, and the citizenry went to war. Even Hank Aaron died. For six years, we’ve been marching through the valley of the shadow of death, and find nothing but plunging cliffs; we’re the unhappiest we’ve ever been, and the happiest we’ll ever be.

But, every once in a while, a light breaks through the clouds and tows us out of our despair. It suspends us above the storm, reminds us of simpler days and better times, and holds us all in a warm rhapsody of relief, joy, and, usually, video games.

Pokémon Go was one such levitation. I was living in San Francisco at the time, and for a few days following the game’s release, it consumed us. We all played obsessively. We celebrated our rare catches. The evening streets were full of roving packs of wide-eyed millennials, chasing virtual lightning bugs. Every bus rider was collecting Zubats.

Though that euphoria didn’t last, a new version is back: Wordle.

True to form, our rapture from 2022 is isolated and online. We play Wordle alone, and—by the hundreds of thousands—post our scores to Twitter, in a simple array of green and yellow emojis.

Are tweets like this annoying? Maybe, though no less annoying than the usual barrage of regurgitated memes that pass for jokes in Twitter’s refinement culture chop shop.1 Do some people hate it? Sure—and some people hated When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go?; there will always be haters. But are these tweets useful? Absolutely. For those of us who are into Wordle,2 they provide a huge dataset for understanding how we play the game—and how we should play.

As someone who’s more comfortable with numbers than words, off I went.

When to panic

I collected about 250,000 games from the last ten days of tweets.3 The overwhelming conclusion that they tell us is this: You shouldn’t lose. More than 96 percent of games are wins, and more than half of them are solved in four or fewer guesses. This distribution is consistent with other analyses (though not with my 88 percent win rate, so I’m already skeptical of everything).

This should calm our nerves when we first start a puzzle—the odds are ever in our favor. But how should we feel halfway through a puzzle? How should we feel, four guesses in, staring at a grid of grayed-out vowels, with only a handful of yellow squares to our credit, and nothing left but ten-point Scrabble letters to choose from? Should we still be calm then?

Given Wordle’s high solve rates, we’re likely still ok. As the chart below shows, after four guesses, people only lose 8 percent of the time. Even when a puzzle comes down to its last guess, loss rates are only 17 percent, nearly identical to your odds of hitting a six on a die in a single roll (or, if you prefer, of rolling a seven in craps).

Of course, this omits a very important detail: How much do we know? If we’re down to one guess, there’s a big difference between knowing four green letters, in which case people lose on their last guess only 7 percent of the time, and knowing one green letter, in which case people lose a third of the time. And if we haven’t gotten any greens and only have one guess left, we’re pretty much sunk. Ninety-three percent of those puzzles end in a loss—although, shoutout to some very impressive saves.

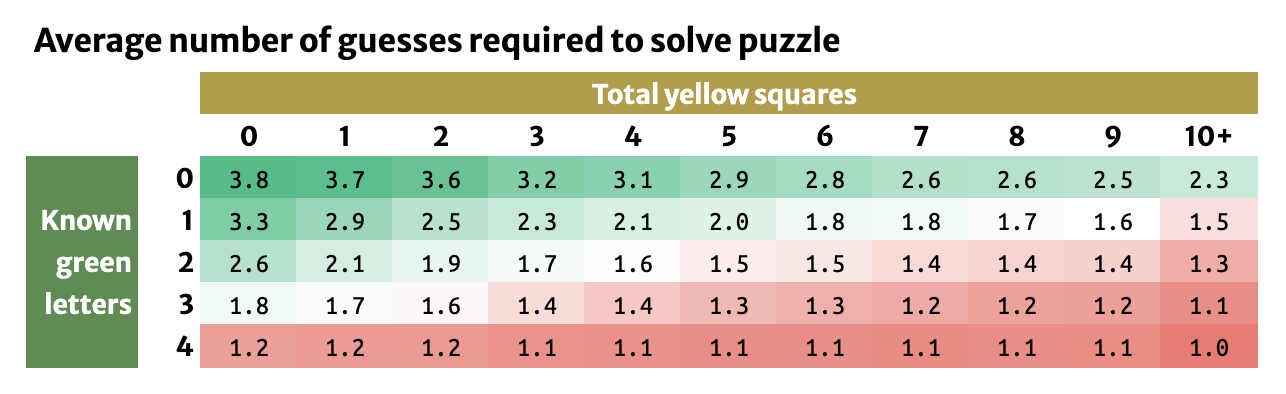

The grid below when when exactly you should panic. First, tally up the number of known green letters (this is the distinct number of positions, out of the five, for which you know the letter). Then, count the total number of yellow squares (in this case, it’s not distinct positions or letters; it’s every yellow square). That entry in the table shows the average number of additional guesses that people typically take to solve the puzzle.

The Panic Grid

For example, this was how I started yesterday’s puzzle. With one known green and two total yellows, I should expect to solve the puzzle in 2.5 guesses. With three remaining, no need to panic yet.

But a lot was riding on my next guess. If my fourth try scored me two yellows and no new greens—giving me one green and four total yellows—I’d be in trouble. I’d typically need 2.1 guesses to solve the puzzle at that point, and would only have two guesses left. Fortunately, my next word had two yellows and two additional greens, giving me a board with three known greens and four total yellows. Saved, for another day.

Hard mode or strategic mode—or both?

Yesterday’s game highlighted a long-standing4 question I’ve had about Wordle strategy: Was “ghoul” a good second guess? After the first guess, the only information I had was one green letter. I could chase the winning word by only guessing words that start with R, or I could play strategically as I did, banking that green letter and using the first position as a way to hunt for more letters. By guessing “ghoul,” I put five new letters in play; if I guessed something that started with an R, I would’ve only been able to test four new letters.

This exact decision comes up frequently. The table below shows the distribution of results for opening guesses. 17.3 percent of the time—in 44,000 of the 250,000 puzzles sampled—people started their game with one green and no yellows. (This is the third most common opening, behind one yellow and no greens, and one of each.)

These people all faced the same choice I did: Guess a word with the same green again, or not?

Wordle, for its part, suggests that the former strategy of guessing the same green letter is more difficult. The game has a setting that requires you to play using that approach, and it’s called “hard mode.” As evidenced by my guess of “ghoul” yesterday, I agree with the game: Sticking with the green letter you know makes you less likely to win.

The masses, however, disagree. Of the 44,000 puzzles that start with one green and no yellows, 86 percent kept using that same green letter—in effect, voluntarily playing on hard mode.5

More importantly—and disturbingly, for my Wordle history—this is the better strategy. People who play the same green lose less frequently, and take fewer guesses to win. Evidently, playing strategically is foolish, and playing on hard mode is easier.

For even more damning proof that the strategic approach is the wrong one, consider three opening scenarios. In all three cases, the player has the same amount of information after two guesses. They know one green letter, and up nine letters that they can exclude. All three scenarios should play out the same. If anything, Scenario 2 should slightly underperform the others, because this scenario can only exclude up to eight letters.

However, all three scenarios actually perform very differently. Games that follow Scenario 1 are more than twice as likely to end in a loss than those that follow Scenario 3. And the only difference between the two scenarios—the only reason the results would be different—is the revealed strategy of the player in Scenario 1.

But…why? Why is the Scenario 1 strategy worse? Why is it worse than even Scenario 2, in which players necessarily have less information? Why is hard mode easier?

There are two answers, I think. First, while the hard mode approach makes it more difficult to come up with words to guess, it restricts you to a smaller corpus of possible words, which likely makes the game easier to solve. Moreover, I suspect that playing this way also nudges you toward words that are “structurally” similar. For example, if you know the second letter is a B, it’s probably more likely that the first letter is a vowel, and always putting a B second improves your chances of finding that vowel.

Second, the biggest benefit of playing strategically and following the approach in Scenario 1 is potentially finding an extra yellow square. But yellow squares just aren’t that valuable. As the Panic Grid shows, adding an extra yellow square to what you know reduces the number of expected guesses remaining by about a tenth of a guess, compared to a half-guess reduction for an extra green. Sacrificing the benefits of playing on hard mode are a steep price to pay for such a small improvement.

In other words, playing strategically might make sense for Masterminds, in which each code is a random sequence of four values. But Wordle is Wordle, not Five-random-letters-dle. The letters aren’t independent. Knowing where one letter goes—and the implications that has on what possible letters could go in other places—is information that shouldn’t be ignored.

The rest of the world, on the other hand—our spiraling catastrophe of isolation and insurrection, of forest fires and fourth waves, of Tom Brady still winning—is a different story. For at least a few minutes a day, beam me out of here, Wordle. Ensconce me in your playful squares, and remind me that “happy” is a five-letter word.

Nobody goes digging looking for dirt

As I was making my way through this data, there are hundreds of different paths I could’ve taken. Some of them were interesting; some boring. Some fit into neat narratives; some were convoluted and confusing. Some were easy to uncover; others required regex.

As is the case with most analyses, I didn’t follow a predetermined route through these decisions. When one particular question proved too hard to answer, I asked a different one. If another result was dull, I discarded it and went looking for something better. And when something was compelling, I stopped and took note.

The final product was a child of these choices. This doesn’t make the analysis wrong, but it makes it something other than objective. It doesn’t mean the conclusions aren’t true, but it means there are a lot of other true things that have been left unsaid.

Andrew Gelman refers to this phenomenon of analysts looking for interesting results as the “garden of forking paths.” The forks are conscious and unconscious decisions we make that draw us towards conclusions of a particular flavor: Controversial, counter-intuitive, statistically significant, worth mentioning. They are the biases in the pegs of our analytical Plinko board, nudging our chip towards the most compelling bins at the bottom. And when we land somewhere mundane, we often don’t bother telling anyone we played.

As analysts, we all do this, all the time. It’s not because we’re lying, cheating, or p-hacking, nor is it because we don’t want to tell the truth. We do it because we want to tell an interesting and meaningful truth.

This, I think, is the hardest part about, as Tristan Handy asks us to consider, saying true things—truth itself isn’t enough. We don’t do analysis to confirm the status quo. We don’t get promoted for figuring out what everyone already knew. Nobody goes digging looking for dirt.

These are the subtle and unavoidable biases that I think Jillian Corkin is correct to highlight in her response to Tristan’s question. No matter how truth-seeking we try to be, the ground will never be truly level. Even if our data is a perfect reflection of reality (which it isn’t) and even if we can act as fully disinterested parties (which we can’t), we still chase—or as readers, remember—the interesting stuff.

One potential solution is to celebrate boring results. Just as academia has popularized replication studies, data teams could encourage analysts to confirm things that we all already assumed. But that’s expensive, and no analyst wants to spend their days retracing someone else’s steps.

The other solution is what Jillian suggests: Talk about it. Put your biases in the open. Acknowledge, if even only briefly, the paths untaken. Don’t let the data “speak for itself;” put the datas into words.

Please take a moment to appreciate the irony that Paul Skallas, the internet’s foremost opponent to refinement culture, a theory that claims today’s society is derivative and unoriginal, was, in the end, a blatant plagiarist.

Into in, casually, not obsessed with it, no, it’s just fun, I’m fine, it’s fine, it’s normal, totally normal, totally fine, I’m definitely fine, what time is it, when is midnight?

This is, it must be noted, both a biased and messy sample. Not every game gets posted on Twitter, and not every post on Twitter is a real game. The first problem is unfortunately unavoidable; the second problem doesn’t appear to be common enough to distort the results.

Yes, it’s been two weeks, but in 2020 2021 2022 time, so two weeks feels like eight months.

Are they actually playing on hard mode? Probably not—only about 3 percent of people typically play that way.

I would imagine that very few people tweet results when they get stumped.

Something I'd love to test about "hard mode" is how many legitimate English words remain after certain green letters. It'd depend on how deeply the game pool dips into the obscure--I'd hope not very far, since that'd be a frustrating experience. I agree that fishing for more individual letters is less useful than reducing the pool of possible words down to a handful. And when you focus on words that might fit, the heuristic-based pattern-matching language parts of your brain engage, which are perhaps better suited to a game like this than quantitative, analytical brain regions. Now I go consider how to get as many letters of RSTLNE in a five-letter word as possible...