Scoring a decade of data predictions

If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again.

Fool me once, shame on you.1 Fool me twice, shame on me.2 Fool me six years in a row, like clockwork, with the same predictions about how we’re on the cusp of turning a corner, how the long anticipation is almost over, and how the waning promise of a once glittering technology will finally be realized—and you might be the founder of a data company, cranking out a list of hastily drafted year-end predictions that, lo and behold, conclude that the product category you’ve been trying to manifest into existence for the last half-decade is about to go mainstream in the enterprise.

I’ve long thought that annual predictions like these were mostly filler, calorically empty content that’s easy to churn out for the sake of publishing self-serving thought leadership, maintaining an editorial calendar, and tossing out clickbait that might catch a viral updraft. Moreover, because we usually forget them as soon as they’re posted, they have little downside—good guesses are the mark of a prophet, and misses are quickly lost to the manic throes of the internet.

But that’s no fun. We now have at least a decade of modern data predictions behind us; why let such a fertile field lie fallow? Let’s see how we did.

“This is our year”

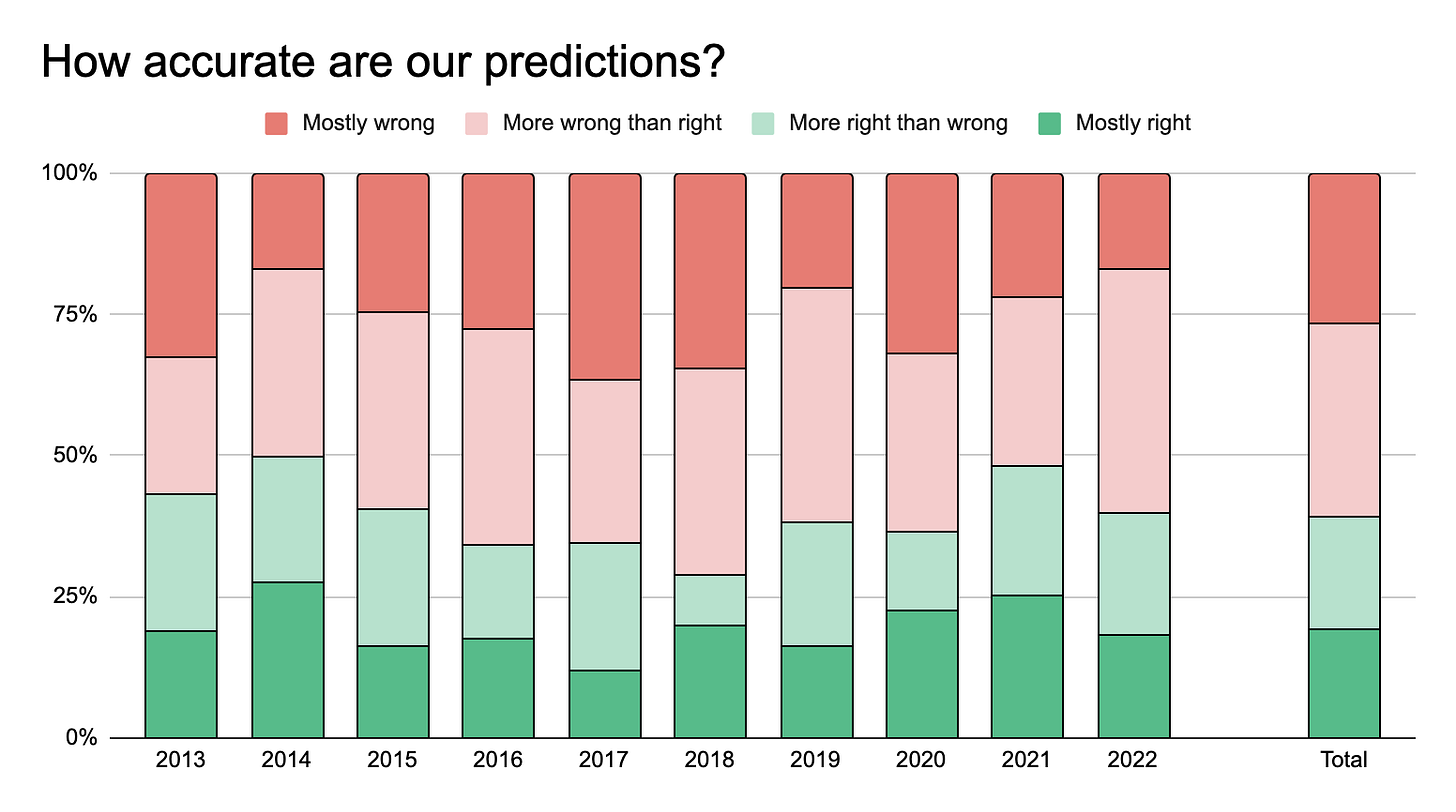

To answer the most sensational question first: Most of our predictions aren’t very good. From 2012 through 2021, I found 79 articles and blog posts containing 635 predictions about the upcoming year.3 Excluding the sixty items that either weren’t really predictions (e.g., ”in 2013, all data is big data”) or were about topics I know nothing about (e.g., ”CIOs will be on the hot seat in 2019”), only twenty percent of the predictions were mostly right. An additional twenty percent were mixed, but more right than wrong; 35 percent were more wrong than right, and the final 25 percent were mostly wrong. In total, I’d estimate that less than half of the nearly 600 predictions issued by various experts over the last ten years could be reasonably scored as correct.4

Is this a bad record? On one hand, predicting the future is hard. The world is a complex place, and forecasts can just as easily get derailed by a madman flapping his wings as by a misunderstanding of the technical guts of the Hadoop distributed file system or a misreading of the trends in the data engineering job market. On the other hand, most of our predictions are vague extrapolations of current trends,5 and don’t require a subtle eye to see. Case in point: forty percent of the mostly right predictions are some version of “the data industry will grow in the cloud.” That’s not exactly going out on a limb.

Still, we can use ten years of predictions to make something other than a spreadsheet that looks like Fruit Stripe gum; we can also use them to create a lens for looking at the road we think is in front of us. In the aggregate, forecasts are a time capsule of conventional expectations. They offer an annual peek into the industry’s zeitgeist, and a contemporary snapshot of where we all thought we were headed. If we’re wrong about 2023—as we surely will be—we’ll likely be wrong in the same ways as we’ve been wrong before.

So how have we missed in the past? We stubbornly predict, year after year, that this is finally the moment some sweeping change bears fruit. For a number of trends—the rise of AI, the importance of predictive analytics, the emergence of data marketplaces, the inevitability of streaming architectures—we’re like a heartbroken Bills fan, half-predicting and half-hoping this is the year for the breakthrough.

Machine learning will establish itself in the enterprise in 2016. In 2019, enterprises will embrace machine learning. In 2021, AI will go mainstream; no, in 2022.

Data monetization will take off in 2016; in 2020, ninety percent of enterprises will generate revenue by selling data; 2022 is the year that data marketplaces explode.

Predictive analytics will become operational in 2014. If you’re not using predictive analytics in 2015, you’re behind the competitive curve. They’ll go mainstream in 2016; there will be progress in 2018; they’ll be a key component in any digital transformation in 2021; by 2022, businesses will be forced to invest in predictive analytics.

Real-time architectures will become more prominent in 2013. They’ll be a must-have for digital winners in 2016; streaming will be reborn in 2017; companies will drive toward real-time in 2018; companies will integrate streaming data directly into reporting and analytics systems in 2020. In 2022, companies will make “just-in-time” data analytics a reality.

2023? This year, I swear, this is our year.

Zeno, Rudi, or Daffy?

There are few ways of looking at our consistent predictions that a better future is coming any day now. The pessimistic take is that we can’t deliver. We either can’t build what we’re promising or people don’t want it.6 All we can do is approach it, like one of Zeno’s runners nearing an unreachable finish line. This can only last for so long; eventually, our strings of misses will come home to roost.

The more neutral interpretation of our forecast record is that it reflects the typical arc of technological progress. To adapt Rudi Dornbusch’s famous quote about economics, “things take longer to happen than you think they will, and then they happen faster than you thought they could.” Our forecasts aren’t wrong, per se, but over-eager. We’ll get there; it’s just hard to know when.

If nothing else, this suggests that an easy trick for making a good forecast is to say that nothing will happen. Though I don't think looking at individual predictions is all that useful,7 one post stood out as being notably prescient: Pete Skomoroch’s predictions for 2014. They were almost all correct, and they were explicitly predictions about what wouldn’t happen. Though this is a bit of a cheat—no matter how good the Bills are, the field will always have better odds—it seems to be the reality we live in.

Finally, there’s also a silver lining in our history of misses. For all the things that we thought would happen that didn’t, there are just as many things that we didn’t think would happen that did. Outside of a few fuzzy nods towards the emergence of a new analytics stack, we didn’t anticipate the explosion of the modern data stack. We thought data would be easier to work with, but had very little to say about the development of new workflows, team structures, or operational standards. In 635 predictions, the potential of DuckDB, the current darling of the data world, wasn’t anywhere to be found.

If past performance is any indicator of future results, 2023 won’t look like we expect. Long-awaited changes, like AI finally delivering on its promise, augmented analytics, streaming platforms, better observability and reliability, data contracts, and the blockchain (yes, this was real), will be slow to materialize—and the longer they take, the less likely they become. But in their absence, new and unexpected things will take their place. Here’s to them being your favorite vendor favored category, finally going mainstream in the enterprise.

It is not the critic who counts

In fairness to this whole exercise, if I'm going to scoff at the skeletons I've unearthed from other people's closets, it only seems fair if I bury a few of my own. So, against my better judgment, here are my six predictions—three safe anti-predictions, three YOLO bets, and six guesses that you’re probably better off ignoring.

We won’t care about data literacy. We’ve been saying data literacy “will go mainstream” for years now. Nothing meaningful happened then, and it won’t happen now. It will skip directly from a buzzword to a throwaway bullet in the Skills section of a resume, alongside “creative problem solver,” “excellent written and verbal communication skills,” and “proficient in Microsoft Word.” We won’t collectively be any better at it; we’ll all just know that we’re supposed to say we’re good at it.

We won’t develop a conscience—or pass meaningful legal frameworks—about AI. The data industry has given lip service to ethical AI for some time now, but when push comes to shove, our better angels usually lose to our bottom line. In this macro, as they say, that won’t change. And until AI becomes a useful political cudgel, policy makers, who are still trying to figure out if Apple products are made by Apple or Google, won’t pass meaningful regulation.

We still won’t find out what a data app is. Data apps—a blinged-out dashboard? A marketing buzzword? Yelp?—have been the low-simmering rage for years now. But we still haven’t agreed on what they are or if we have them yet. This won’t change in 2023. We’ll continue to define them through the Mirror of Erised—as an imaginary reflection of what we wish they were.

A data skeptic movement emerges. After twenty years of unquestionably accepting that “data driven companies win,” an opposing school of thought will begin advocating for company leaders to rely more on their instincts. Executives will point out that Steve Jobs never cared about focus groups; they will make poorly-aging arguments about how quickly Elon Musk makes decisions. Substack writers will shill for clicks by posting inflammatory headlines asking if data-driven companies win. An HBR study, based on an informal survey of 32 CEOs, will get published that shows that they do not. Someone will make the comparison between data and “the science.” It will get ugly.

Salesforce acquires Fivetran. Salesforce clearly wants to be the hub for enterprise applications. Fivetran becomes its tentacles, pulling data from every other vendor into Salesforce's empire. Fivetran adds Salesforce itself as a destination. Salesforce, says Salesforce, should be the brain of your business, not a database.

The breakout product of the year is Modal. Data people tend to be capable at writing code and terrible at deploying it. By helping address this latter problem, Modal—”lambdas, but better”—will become the pretengineer’s (read: data scientist’s) way of using tools like stable diffusion, ChatGPT, and DuckDB. Their popularity will become Modal’s popularity.8

No, really, shame on me for pulling this stunt twice.

To find these posts, I googled “data predictions 2012” (or 2013, 2014, and so on), and clicked through on the top results until I’d found between 50 and 75 individual predictions. This obviously isn’t a particularly rigorous way to gather predictions, but the sample size is large enough (and Google’s rankings probably good enough) that the forecasts are relatively representative of conventional wisdom.

Obviously, judging whether or not a prediction is right is a subjective exercise. Given the number, I did it fairly quickly. Nor did I carefully consider all the paragraphs-long caveats to each; instead, I tried to judge the overall thrust and spirit of each one. For example, one post predicted that we’ll have better mobile BI: “Rather than elaborate visualizations, you will see hard numbers, simple graphs and conclusions,” and on “wearable devices you might look at an employee and quickly see the key performance indicator.” Though mobile BI has surely improved, I see this prediction as a miss because BI hasn’t shifted in the way that was described. All that said, if you disagree with my assessments, fair enough. Hit me up.

Gartner, of all places, is an exception. A lot of predictions are barely comprehensible gestures in the direction of indeterminate destinations, like SAS’s prediction that, in 2016, “big data has moved beyond the hype to provide real value.” Gartner’s predictions are quantified, time-bound, and use (for the most part) nouns that have definitions. Credit where credit is due.

In this way, we aren’t like Bills fans, hoping for a championship. We’re like Bills players, promising a Super Bowl, and then failing to get it done on the field.

They’re like polls: Aggregate them, and don’t cherry pick your favorites.

I’m a personal investor in Modal, so consider this prediction to be calorically empty content that’s easy to churn out for the sake of publishing thought leadership that ends with a self-serving conclusion.