The more the merrier

Steal this writing process, and join me on the dance floor.

I should start off by saying that I have no idea what I’m doing. My formal writing education started and stopped with the five-paragraph essay, a sentence-by-sentence recipe taught to North Carolina public school students for the sake of passing a seventh grade writing test. Ever since that test, and the weekly essays we hand-wrote to prepare for it, I rejected the entire enterprise. I wish I could say I did it because the formula was stifling, and I refused to cram such a creative endeavor into a standardized 34-sentence box. But that’s not true. I ran away from it because I nearly failed the test. Embarrassed and frustrated, I became a “math person,” the teenage precursor to a professional “data person.”

I outran the ghost of my “needs improvement” score for fifteen years. I studied math and economics in college, in no small part because those classes didn’t require me to write papers. I took jobs that wanted me to communicate in plots rather than prose. I embraced spreadsheets, Nate Silver, and (obnoxiously) lecturing people about the need to think probabilistically.

But in 2013, I ran out of places to hide. In the months immediately following Mode’s founding, there was no math for me to do. We had no customers, no users, no product, and no data—and I, as the person appointed to analyze it, had no job. So I found myself writing blog posts.

The leap was less uncomfortable than I expected. In college, a rare essay meant burying myself in the library stacks, tweaking on free Folgers and creamer, and racing 3,000 words on social choice1 to a 9 a.m finish line. The Mode blog—and now, this Substack, and its informal Friday deadline2—has required a lot less caffeine, fewer all-nighters, and has been, in the biggest surprise of all, kind of fun?

My newfound amusement in writing these pieces comes in part from wriggling free of the seventh grade straightjacket. Rather than writing to impress an underpaid and faceless assembly-line grader forced to score thousands of templated essays against a manufactured rubric created by an overpaid and faceless administrative state committee, I started doing it to entertain myself. I wrote about what I was interested in, told the stories I wanted to share, and made the jokes I thought were funny. I don’t know if 400-word detours through tangential stories about middle school or footnotes about Griff3 would’ve helped my score back then (though they couldn’t have hurt), but now, that’s the good stuff that helps me forget about the messes I used to make.

The other nice thing about this Substack—also missing from seventh grade essays—is an audience. You can only shout into the abyss for so long, and I’m very grateful to anyone and everyone who’s shouted back.

My hope for 2022 is to shout with more of you. My hope is that new blogs like Ashley Sherwood’s and Emily Thompson’s start a much bigger avalanche, for the sake of the community finding new voices, for the sake of others finding the same unexpected satisfaction in it that I did, and, selfishly, for the sake of me having more people like Ashley and Emily to find inspiration in.

To the folks on the edge of the dance floor—please, join us. I understand the hesitation: It’s hard to stare down a blank page; it’s hard to know what to talk about; it’s hard to imagine people will read it, much less like it; it’s hard to see yourself as someone with a blog; it’s hard to know what you’re niche is, or what to call it.

I clearly can’t help with the last problem. But on the others, I’ve figured out some things that work for me (to the extent that you do or don’t judge anything here as working). If you’re thinking about being part of the party, take what’s useful, discard what isn’t, and let’s dance. In the words of Nate Dogg,4 even if you feel like you’ve got two left feet, it’s real easy if you follow the beat.

This is my beat.

TikTok, not Twitter

People tend to equate blogging to Twitter, seeing the former as an extended version of the latter. To me, it’s a bad analogy. Twitter encourages a kind of pseudo-intellectual arms race, a back-and-forth dunking on one another, with everyone seemingly trying to prove they’re the smartest person on the internet. On Twitter, it pays to appear to be the most contrarian.

TikTok, by contrast, is almost overwhelmingly derivative. The entire app is built to help creators riff on one another, react to one another, and repackage trends and challenges into new variations. Thumb through TikTok for an hour, and you’ll see the same joke told over and over again. And yet, it’s TikTok, not Twitter, that’s the most popular website in the world.

The magic of TikTok’s medium is that it’s built around stories, not takes. It’s emotional, not intellectual. It celebrates people for their trademark individually, not for how smart they are. We don’t doomscroll on TikTok; we just scroll.

I think blogging should be the same. Rather than chase new ideas, or feel the pressure to make everything original, I try to accept that everything’s already been said.5 Old stories, told from a new perspective (i.e., with new analogies), can still find an audience.

The good news is coming up with things to say gets easier as you go. Posts begat conversations, conversations begat ideas, and ideas begat posts. In this sense, blogs become self-sustaining, with each post planting the seeds for the next one.6

Bullets kill

Once I have an idea, it is with great regret and self-loathing that I have to agree with The Writing Guy™7: I write as much about it as I can, as quickly as I can. I don’t think of this as a first draft, but an opening conversation.

However, unlike what’s suggested by “Pixel method,” my version of this phase is more appropriately described as, to borrow the language of Silicon Valley, the rubber duck method. The goal isn’t to position a bunch of sentences to be refined later; it’s to wander through an idea, and see where it takes me. I approach it as though I’ve been asked a question and I have to not only answer it out loud, in full sentences, but I also have to filibuster for ten minutes when doing it.

This isn’t an entirely original idea either, though I think “write to someone else” is an insufficient bit of advice. The point isn’t to narrow your audience, or to talk to one person; the point is to be conversational and to skip the literary preamble. It’s to imagine someone asking me, “What’s your opinion on Taylor Swift?” over dinner, and I’m answering the question without worrying about organizing ideas coherently or coming up with a clever opening line.

Critically, I write this in full paragraphs and not bullets. No bullets; never bullets. Bullets cut ideas short. They let me glance at something and convince myself I’ve seen it, while staying comfortably on my original path through a topic. But the most interesting things are off the trail, viewed carefully and up close.

Bullets also frame the exercise as drafting an outline. At this stage of the process, outlines are deadly. I don’t want to worry about structure; I don’t want to think about narrative threads; I don’t want to trace the lines to color in later. Quite the opposite: I often don’t even know what I’m drawing yet.

To help with this, I typically dictate this “conversation” in a code editor like Sublime instead of Word or Google Docs. This isn’t about avoiding the distractions of the internet—I still constantly command-tab to Chrome, no Slack, no Spotify, no Chrome, no Slack, no Chrome, no Slack, no Chrome, no Slack, no Chrome, no Slack, no Spotify, no…TikTok?, no, fine, back to the text editor. Instead, I use Sublime to avoid the need for polish. I don’t want to correct misspelled words or fix grammatical errors, nor do I want to worry about formatting. I just want ideas on paper.

This phase is often fast, just as an actual conversation would be. I usually do it in one or two sittings, each taking less than half an hour. For this post, I did this in about twenty minutes, and produced a fairly typical collection of messy, rambling ideas.

Like it twice

My next step is to walk away. I don’t want to get the topic out of my head—once the mental trains are moving, they’re hard to stop anyway—but reset the narrative. Inevitably, in the course of shotgunning ideas at a page, some structure starts to take shape. Usually, it’s a bad one, ill-considered and half-formed. Away from the paper, I try to find better narrative studs. What story can I hang the main idea off of? Could something make a good hook? Are there any analogies or turns of phrase I particularly like?

I usually bounce through a few iterations, and try to find a structure I like twice—when I first think of it, and again, later, after the thrill of its novelty wears off. Once I have something I like (or, more realistically, can tolerate), I return to the original doc, and type a shallow outline at the top.

I use bullets, usually fifteen or so, each about a sentence long. At this stage, I want to lay out the major points of the plot—say this, then this, then this. Bullets keep me from getting lost in the wording. But it’s still not a proper outline, with sections and headers and multiple levels of indentation.

It’s also not a summary of the ideas I wrote down in the first phase. That collection is just a that—a collection to draw from, a grab bag, an unordered list. They’re ingredients, and the bullets—like these, created for this post—begin to sketch out a recipe based on the good ones.

A slowly building panic

Next, the real work starts.

Using the bulleted list as a thin storyboard, I try to write a first draft. I draw from the knot of ideas I first wrote, though I never copy from it directly. Those ideas were written without knowing where the story was going; by typing them again, I can rework the details that hold the plot together.

This is also the point I start to apply some polish (and therefore, when I copy everything into a Google Doc). I’ll linger on sentences and syntactic choices, sometimes finding things I like, and sometimes settling on something that’s good enough to hold the idea and advance the story.

As I’m doing this, I work the doc into four loose sections. The actual draft is at the top, slowly building down from the narrative outline. That outline sits below it, and all of the original notes below that. I delete bullets and ideas, sentence by sentence, from the middle two sections as they’re incorporated; over time, those sections shrink as the draft grows. And ideas or phrases that I like but can’t find a place for are added to a list—the fourth section—at the bottom.

I suspect this is all weirdly pedantic, but I’ve found it helps keep my station clean through the messiest and hardest stage of the writing process. Because if a post falls apart (read: if I fall apart), this is when it happens. This transition is when you find out if the design of the post’s bones will hold the weight of its body—and often, it doesn’t. You find a point that needs to get made twice in different places; a transition that doesn’t work; a key story that takes too long to tell.

These lumps can sometimes be massaged out, like a tight calf on a foam roller. But not always. If you grind through a sore spot and it never loosens up, the problem may not be the muscle, but the bone. In these moments, which are hard to recognize and harder to accept, you sometimes have to kill your darlings, and redesign the entire skeleton.

Without exception, these are the darkest hours (or days) of every post. They’re the periods of the doubt and grinding despair, when when I’m working through the details but nothing is certain. It’s writing via dead reckoning, plotting the course of each paragraph based on the preceding one, but not yet knowing if anything is headed in the correct direction.

Fortunately, this also suggests a solution: Find a fixed star. Once I can anchor myself to a title, an opening line, or a short passage that I know is right, navigating the rest of the post is much easier.8

Beginning with that star, the piece finally takes shape. Ideas I like turn into paragraphs I like, which turn into sections I like. This is also when I usually figure out the tone of the piece. Is it long and melodramatic? Short9 and punchy, serious, personal, technical, distant? I usually find this voice in the phrases that I like, or in the rhythm of the scenes I don’t want to cut.

“Until you can stand it”

Once the studs are set, the rest is polish. In this final stage, the best advice I’ve heard is from Jia Tolentino (via, again, Angela): “Read it over and over again until you can stand to read it.”

Like listening to our own voice, most of us instinctively wince at what we write. It’s easy to excuse that as some mix of self-criticism and imposter syndrome, as an inevitable inconvenience that makes us incapable of assessing our own work.

This, I think, is wrong. As Tolentino suggests, you can like it—it just takes work. If a sentence is clunky, write it again. If it’s still clunky, write it again. Over and over until you truly, honestly, like it. This can be a grind (again), but no great piece of furniture was made when the carpenter got tired of sanding it; it was made great when the carpenter finally liked how it felt.

Deadlines being what they are, not everything turns out great. I’ve written as many things for this blog that I hate as I love. But it’s useful to know I can love it, if only I put in the time to do it.

Appointing yourself as your own judge has one other benefit: It helps pieces keep their character. Not everyone will get every joke or follow every reference, and that’s ok. If it’s fun for me to write, maybe it’ll be fun for other people to read.10 Edit, but don’t sterilize.

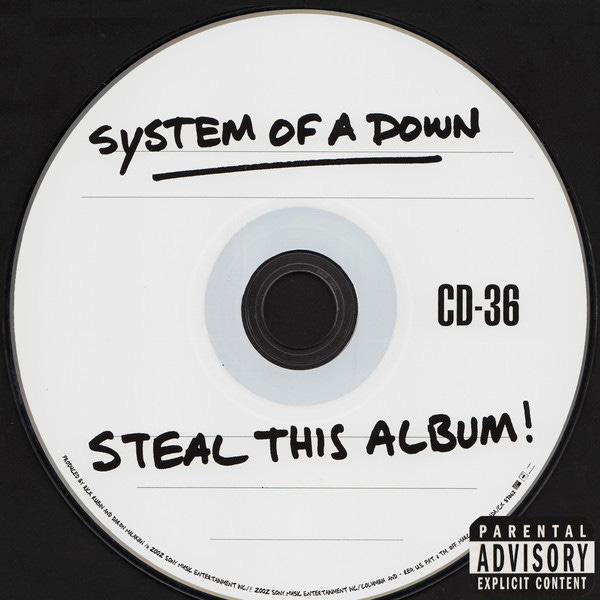

The only New Year’s resolution I ever made that stuck was one that I stole (thanks Aroop; after eleven years, still going strong). To the more resolute out there, debating if now’s the time to join the conversation, please, repay the favor and steal this album. The remake is often better than the original.

On one hand, I’ll never forgive you, Dr. Heckelman, for sneaking multiple papers into an econ class. On the other hand, you taught me about Arrow’s impossibility theorem, which is a very cool theorem. So we’ll call it even.

The whole Friday thing was half accident, half Angela Wu Li seeing the unconventional potential in the vibe of arguing about data on Fridays. And speaking of Angela, everyone should follow her (all-too-infrequently) updated Substack, human not dancer. Compared to this one, it’s better written, has much better musical tastes, and is considerably more, well, human.

As I was saying about this Substack’s musical tastes…

As I was saying about this Substack’s musical tastes…

And in data, there’s really only one thing to say.

This post, in fact, came from a conversation I had with two people in the data community.

Twitter is full of con jobs, but one of the most irritating (and, in fairness, probably least harmful) is the Born Again Hustle Horoscope. They’re all written by Very Online combinations of Tony Robbins and get-rich-quick stock brokers, each with their own beat—Writing! Spiky POVs! Growth frameworks! “Deconstructing things”!—and backstory, typically about having survived the corporate grind to reemerge as an enlightened sphinx, full of borrowed and bite-sized proverbs packaged into threads of punchy multi-line tweets that always end feeling vaguely like a Ponzi scheme: “For more threads of unconventional wisdom, subscribe to my newsletter The Courage to be Candid!” These threads, which often read like ironic and self-contradicting riddles, are too trite to be helpful, and instead seem to prey on the dissatisfaction of the college-educated millennial who’s got two-coffee-a-day hustle, a good resume, and a well-paying desk job that they know, know, is holding them back from their true potential. It’s grift, shallow inspiration and no substance, written for retweets rather than actual reinventions, 280 characters about owls and lessons on how to draw two circles, with nothing in between.

Unfortunately, I rarely know if I like something until it’s fully formed, which is why formal outlines don’t work for me. This process would be much easier if I could fix a bunch of stars with an outline, and then add the details around them. But without those details, I can never tell if the stars are actually good.

“There are short pieces?,” the confused reader says.

“It’s not,” the exhausted reader says.

I didn't know you were doing substack until today when Angela shared the link. Looks like I am months and months behind the times. This adds context to the conversation we had in New York about writing and substacks. Great post. Can't believe you held out on sharing the New Year's resolution with us?!?

Happy New Year Benn! Thanks for this detailed process, no excuses for not writing any more :-) Do you sometimes prefer to get your final piece read over by someone, or do you always go by your own judgement?