Who is “the community?”

It has the potential to be one of the data industry’s biggest perks—and its highest walls.

The analytics community, ironically, didn’t listen to the odds.

Years ago, when it was first coming together, it wasn’t likely to go well. Internet communities, especially those dominated by young men, tilt toward poisonous cesspools.1 Analysts are generally a prickly bunch, and in the first half of the 2010s, our anointed king was a professional “well, ackshually” contrarian. And the cultures of two of the data industry’s closest adjacencies—startups and software engineering—are toxic to many of their members.

But the early pioneers in the analytics community broke the other way, drawing cultural inspiration from places like R user groups. The R crowd is well-known for striving to be inclusive, for welcoming women, and for protecting its own members. The data community that formed in the years that followed has built a similar reputation. Even in my experience as the apparent modern data stack bully, online groups have been nothing but professionally supportive and personally welcoming.

These benefits, however, aren’t shared equally. In particular, if you look around community spaces—the conferences, the Slack channels, the meetups, the Twitter conversations, and, one assumes, the data teams inside companies—black people are woefully underrepresented.

Over the last couple years, a handful of organizations have sponsored about a dozen community-oriented data conferences. Unlike the big pay-to-play trade shows that are dominated by hanger-sized expo halls and on-stage infomercials,2 these conferences aim to attract and promote community leaders. In this regard, they’re representative of both who the community is and who the community aspires to be.

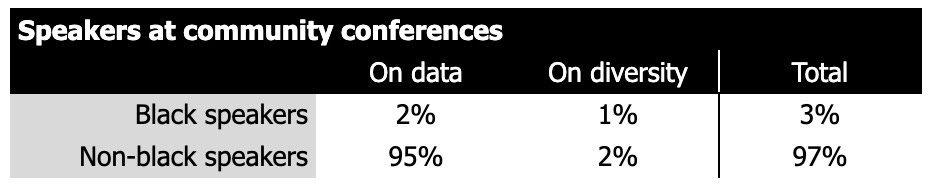

Out of a total of over 500 speakers at these conferences, less than three percent are black3—a third of whom spoke about diversity.

Moreover, these dismal numbers are, if anything, inflated: Nearly all of these conferences' hosts promote diversity in some fashion. Some of them prioritize underrepresented groups when choosing speakers. Some explicitly highlight diversity at the center of their promotional materials. And all of them have codes of conduct meant to protect people from the kind of harassment that’s common at tech conferences.

Other surveys confirm the same trend. Though companies don’t publish exact figures for data teams, Harnham, a data recruiting firm, reports that three percent of data and analytics professionals are black.

That, it seems, is where the community is. On one hand, it’s well-intentioned, bucking some of the worst tendencies of other internet groups, and a launching pad for many friendships and careers. On the other hand, those benefits are just as concentrated among privileged groups as the rest of the tech industry’s are. According to their most recent reports, black people account for 1.7 percent of Facebook’s tech workers4 and 2.9 percent of Google’s—figures nearly identical to those in the data community.5

I could, as is true in any conversation about diversity, make the case that these low numbers are a business problem. Diverse teams, I could say, are smarter. They’re more innovative. They make more money.

While I agree with these points, I disagree with the premise on which they depend: that diversity is about the bottom line. Drawing connections between diversity and shareholder value will always be somewhat tenuous, and, if we concede that such a connection is necessary, some people will find easy ways to object.

Instead, we should be comfortable making the argument that inclusivity and integration are important on their own merits. People shouldn’t be shut out from the opportunity to be part of a rewarding community and a lucrative career. Nor should people be comfortable in exclusionary or segregated spaces, especially when those spaces could confer special benefits and advantages to their members.

Beyond that, the lack of black representation in data science, machine learning, and AI is particularly dangerous. There are many well-documented stories about data science teams embedding latent racism and bigotry into their models, hurting black people’s ability to get loans, interfering with their health care, rejecting them from jobs, identifying them as carrying guns they don’t have, and charging them with crimes they didn’t commit.

These problems don’t just cause obvious and irreversible harm to their victims. As more and more decisions get automated,6 programmatic prejudices reinforce themselves, creating additional biased outcomes—in everything from who gets admitted to college to who gets reviewed for parole to the vernacular that chatbots understand to how bus routes are designed—for future models to train against. They turn systemic racism into systematic racism, encoded and executed automatically, relentlessly, at scale.

The effects of underrepresentation in the broader analytics community are harder to see, but no less damaging. Racism is durable in part because it evolves so efficiently to both code “unfavorable” traits as black, and to code “black” traits as unfavorable. Whenever society gets close to inoculating itself against a particular racist trope, a new strain emerges.

With data, the conspiracy is already at work. The cliché that all jobs will soon be data jobs elevates quantitative reasoning—a skill set that is, not so coincidentally, seen as white and male—above other skills. This bias is reinforced by the demographics of the data community, creating a vicious cycle that holds black people out of power and punches out a back door for white men. Unless the community becomes more visibly diverse, “data literacy” could become one of racism’s most powerful professional variants—and the analytics community could, even inadvertently, be one of its most forceful accelerants.

None of this, frankly, should be a surprise. Racial power structures are embedded in everything, and data is no different.

But, if everyone knows it, very few people in the analytics community talk about it. It’s not even brushed under the rug, like an open secret that it’s impolite to talk about. Instead, it’s a blind spot, an unacknowledged problem that’s largely ignored, save the occasional blog post, perfunctory diversity panel, or statement pledging to “do more.”

This shows the limits of self-perceived kindness and progressivism. The data community prides itself on being open and welcoming of new members; for many people, it is. It’s also spun out countless organizations and projects that aspire to help civic groups use public data for social good; these efforts, I believe, are genuine. Despite that, underrepresented groups still have to carry their own water. As the earlier table shows, black people are invited to conferences to talk about diversity; everyone else gets to talk about data.

This needs to change. There is no long arc toward equality without broader effort—and being “nice” isn’t enough. A culture of congeniality can be just as ruthlessly biased as a toxic one, while also being better disguising its closed doors.

Furthermore, data professionals, who have a habit of dismissing people they see as emotional or irrational, should be cognizant of how they define what’s reasonable and what isn’t. Analysts aren’t infallible logicians, arriving at their position through a detached reading of The Numbers. We’re all products of our environments, and we really, truly, can’t detach ourselves from it.

This compels people to look at some arguments—how a lot of white people view, say, defunding the police—as inherently extreme, no matter how much data is marshalled to support them. Other positions, like those that tweak but don’t upend the status quo, are seen as disciplined and impartial on their face. It’s telling that we characterize how “reasonable” a solution is by how moderate it is, rather than how effective it may be. It’s telling that people only say “let’s be reasonable” when they want to keep things the way they are.

Analytical communities built subtle walls on top of biases like these. People who can afford to present sober analyses in inside voices are celebrated; people who argue forcefully for bigger changes are discounted—and in some cases, outright fired.

The data industry has the money to do more. It remains to be seen if it has the commitment.

Or, to keep with the early theme, wretched hives of scum and villainy.

Welcome to our session, “How MapR™ is enabling enterprise digital transformation,” led by the chief customer officer of MapR™, sponsored by platinum partner MapR™! Join us after the session in the MapR™ Sapphire lounge for our fun happy hour event, “Pinot Noir and MapR™!”

Notably, the distribution isn’t uniform. About six percent of the speakers at Coalesce, dbt Labs’ conference, are black. Excluding Coalesce, less than two percent of speakers are black.

For comparison, gender splits are slightly better in the analytics community. At both Facebook and Google, 25 percent of tech workers are women. Harnham reports that 27 percent of analysts are women; I estimate that 30 percent of data conference speakers are women.

Except those personally valued by investors.