Producer theory

Platforms are overrated.

You know you’ve thought about it:

You create a startup to solve some specific business problem, like helping people schedule meetings, or write better advertising copy, or understand how engaged their employees are. Since it’s 2025, you want to solve the problem with an “agent”—that is, approximately, a chatbot that automatically completes tasks. Your customers will tell it who they want to meet, or what they want to sell, or what their employees said about them in their latest engagement survey, and your bot will schedule their meeting, or create their ad, or tell them that their employees do not particularly care for the new work-from-home policy.

When you build the first version of your product, it is a wrapper around ChatGPT. Sure, it’s a complicated wrapper—there are many clever prompts; the prompts’ results are passed into other clever prompts; it’s a loop of self-reflective prompts; it’s reasoning; it’s agentic; is this AGI?—but, still. You can only coax so much performance out of the machines, because your product’s capabilities are fundamentally dependent on the intelligence of the foundational models underneath it.

This troubles you. First, every other startup that is helping people schedule meetings, or write better advertising copy, or understand how engaged their employees are is building their agent in the same way. What if they write better prompts? What if your clever prompts leak? It would be bad. Second, the frontier models keep improving.1 That’s good, until it becomes very bad. Smart models make your product better, but too smart models make it obsolete. After all, how valuable are your clever prompts about how to write good ads if ChatGPT can write good ads all on its own? And third—and most glaringly—your prompts don’t really work anyway. Your agent keeps making annoying mistakes. When it schedules meetings, it doesn’t know which other meetings can be moved and which can’t. The copy it writes is generic, and doesn’t reflect your customers’ fun and quirky brands. And it expresses a deep concern about employees who constantly call their coworkers fools.

Fortunately, you can solve all of these problems with a single solution: You will give your agents more context. Because context is key. Because they say there is no AI strategy without a data strategy, so there can’t be an AI product strategy without a context strategy. Because, to be good at scheduling someone’s meetings, your product needs to understand what else they’ve been working on recently. Or to write fun and quirky advertising copy, you need to understand the fun and quirky ways businesses are already interacting with their customers. Or to analyze employee engagement surveys, you need to know more about how employees talk to each other.

So you build connectors into other services—your product ingests your customers’ emails, Slack messages, Google Docs, Notion docs, Zendesk tickets, Jira tickets, and Linear tickets. It connects to their Salesforces and Saleslofts and Boxes and Dropboxes and Zooms and ZoomInfos and InfoZooms. It integrates with their data warehouses. Your website says that your service connects to many sources, to dozens of sources, to more than a hundred sources, and new ones are being added all the time.2 It says that you connect to an industry-leading number of sources.

But…if you connect to the most sources…and everyone else is trying to connect to those same sources too…and you’re already doing the hard work of ingesting all of this data and compressing it into “context”...why not…sell…that? Rather than being a dreaded point solution that just schedules meetings or writes ads or contemplates how engaged employees are, other agents will ask you for context—what are Geoff’s scheduling preferences? What brand voice resonates the most with customers? What is this, a company for ants?3 If you integrate all the data, you can become a data provider. You can become the MCP everyone else uses. You can become A Platform.4

It’s all a bit weirder than that, though, because the “standards” are circular. Notion ingests conversations from Slack; Slack ingests documents from Notion; both use OpenAI or Anthropic to provide their AI features, which themselves both offer native connectors to ingest conversations from Slack and documents from Notion. The Jasper AI platform learns how to write ads for you by learning from those same documents, and then makes that context available to other products, like bots that write copy in, again, those documents. Lots of startups aggregate and integrate context together, and then make it available via MCP, to be consumed by another product that will aggregate and integrate it again. It’s platforms, all the way down.

You could have a couple theories about all of this, I suppose. One is that integrating all of this data together is extremely valuable, and that the rush to do it—according to The Information, every major enterprise software company is building an “enterprise search” agent—is a very sensible war for a very strategic space. Google became the fourth biggest company in the world by being the front door for the internet; of course everyone wants to be the front door for work. And this messiness is just an intermediate state, until someone wins or we all run out of money.

A second theory, however, is that platforms aren’t as valuable as we think they are. For a decade now, Silicon Valley has come to accept, nearly as a matter of law, that the aggregators are the internet’s biggest winners. But aggregation theory5 assumes that production flows cleanly from left to right: From producers, to distributors, to consumers, with the potential for gatekeepers along the way. “Context”—especially if MCP succeeds in making it easy for one tool to talk to another—is not like that. Slack aggregates what Notion knows; Notion aggregates what Slack knows; ChatGPT aggregates what everyone knows, and everyone uses ChatGPT to aggregate everything. Producers are consumers, consumers become producers, and everyone is a distributor. There aren’t people orderly walking into one big front door; there are agents crisscrossing through hundreds of side doors.

In that telling, the right analogy for context isn’t content, but knowledge. Because what is context, anyway? It could be a pileup of Google Docs and emails, but it’s also things that are derived from that information—the preferences of how someone manages their meetings, and the unspoken style guide that’s implied from a thousand marketing emails, and the loosely combined summaries of what employees are saying in engagement surveys.

If you squint at these context ecosystems, they are a bunch of tools that are trying to learn from each other. The most valuable nodes aren’t the tools that aggregate the most information and offer it up for easy consumption, but the ones that push the most new intelligence back to the group—either by being a unique source of raw information, or by learning clever new things from other people’s information.

Arguably, that’s what a lot of these tools are already doing—some are collecting, and some aggregating and enriching, or aggregating and compressing.6 But in our obsession with becoming platforms, we might be surprised by how valuable it is to stay “just” a producer.

You put these logos on your website, and it’s a little bit unclear if they’re integrations or customers. This may or may not be intentional.

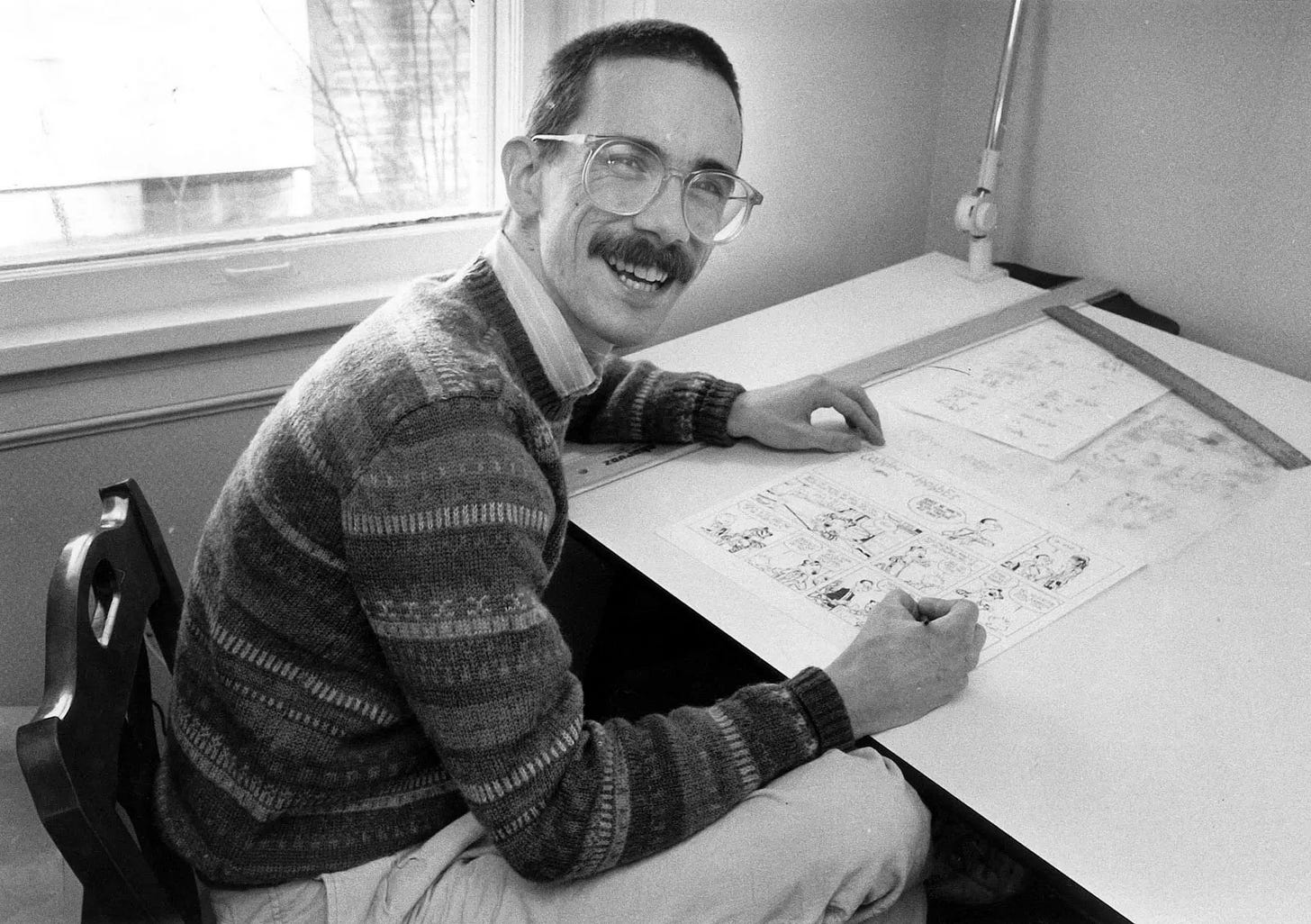

“The company has to be at least three times bigger than this!” (“And he’s…absolutely right?”)

There are variants to this story, of course. Some companies start as natural aggregators of data, and softly pivot into becoming context layers for AI. Some companies already host valuable information, like documents or conversations, and begin incorporating other sources into their products’ search. Some companies are really big, and buy some connectors and a search engine.

I can’t succinctly explain aggregation theory because I’ve never quite understood aggregation theory, but to do the best I can: Before the internet, distribution was expensive, so consumers had limited choice, so suppliers, who controlled or owned distribution channels, had a lot of market power. After the internet, distribution was cheap, so consumers had tons of choice, so aggregators—companies like Google that sat between consumers and suppliers, and could control or influence what they chose—had all the power.

Which could be a disaster, I should say. Every tool reads from the same primary sources, they all “learn” from each other, their confusion compounds, and the enterprise agentic workforce is a blurry JPEG of two Google Docs.

Ever think about how much electricity we're wasting putting the same content through various models again and again? Slack putting Notion content in models. Notion putting Notion content in models. Glean putting Notion content in models.

Argh... the amount of energy wasted.

And then you see players like zo.computer trying to bring back myspace/xanga culture to the internet again: tribal curation.

That's the one play I see companies trying to capitalize on: a seedling in the zeitgeist where people want to own their corner of the internet again (and make money with curated access and zero-sum status games).

It's the same thing I see with warehouse party culture in LA. "What's the password to get in?"