Live like you’re dying

A short life on a campaign.

An old friend and I used to have a joke, back when both of us were still working at a startup: “She’s not gonna let us out.”

It was taken from the Perfect Storm, right at the end. (Spoiler alert, but it’s a twenty year-old movie, so if you don’t know it by now, I don’t know what to tell you.) Captain George Clooney and his crew have been stuck in the middle of a category five hundred hurricane for the whole movie, and their boat is falling apart. Their radio blew away, their anchor fell off, and they’re running out of supplies. They are losing hope. Then, for a moment, the waters calm and the sun breaks through the clouds. They stare at it; the music lifts; Mark Wahlberg says, “We’re gonna make it.”

But almost immediately, the clouds close again, and the ocean reignites itself. George Clooney says “she’s not gonna let us out,” an enormous rogue wave appears in front of them, they kamikaze halfway up it, crash, sink, and die.

Between my friend and I, it became a meme:

Fill in the second frame with whatever you want: An important hire; a banger of a quarter; “our biggest product release yet.” For a moment, we thought it was going to get easier. The calvary was coming; the boulder was reaching the top of the hill. But, no. The escape was an illusion, a mirage, the calm in the eye of an eternal hurricane. We weren’t out, but still, always, sailing towards the storm.

—

Despite their reputation, startups are not always an especially acute amount of work; twenty-four year-old investment banking analysts regularly put in more hours. Nor are startup employees under uniquely extreme stress; medical residents are making life-or-death decisions, not the people running a nascent software business that sells productivity tools to other nascent software businesses. And while fishermen risk life and limb sailing through deadly hurricanes to make enough money to survive, we sit at computers in comfortable offices—or just at home—in hopes of making obscene amounts of money, because making merely embarrassing amounts of money at Google isn’t purposeful enough.

Still, there is one tax that startups impose that other careers largely do not: Uncertainty. Not uncertainty of success—that’s everywhere, and if anything, it’s easier to fail up in Silicon Valley than it is in most places—but uncertainty of tenure. There is no scheduled graduation date, no annual offseason, and no two-year analyst cycle. There are milestones, like raising money and moving into new offices and crossing revenue thresholds, but the old VC trope—”now the real work begins!,” after you close a venture round—is guttingly true: These things are debts.1 They are promises to grow into; they are commitments to keep sprinting.

But that’s the paradox of a startup: It isn’t forever. They aren’t maintenance projects; they are rarely our last careers. They do, in fact, have a finish line—an acquisition, a graceful transition to becoming the chairman of the board, an opportunity to spend more time with your family, an implosion, bankruptcy, the sweet relief of death.2 You just don’t know where it is.

So another friend and I had a different joke: "It'll get better in two weeks."

This week? A lost cause, bulldozed by the current thing—an important deal going sideways; a festering beef between coworkers; a board presentation; a pileup of calls and Slack messages; whatever. Next week? A traffic jam from this week, of rescheduled meetings and punted follow-ups. But the next week? Then, we joked, things would calm down. Then, we will catch up on emails, and errands, and sleep. We will go home, log off, touch grass. In two weeks, the gridlock will clear up, and there will be nothing left but an open road, and a whole lot of speed.

It’s a delusion, of course; we knew it was a delusion. That’s not how startups work. Inevitably, the calendar fills itself up again; a different customer has a different crisis; new people start a new beef. The ocean reignites itself. We knew the finish line was a mirage on the horizon; it was free beer, tomorrow.

But you need the delusion, because you can’t run a marathon of sprints without convincing yourself that a finish line might be around the next corner. You need to believe that maybe this time is different. A new hire is supposed to take over one of your projects. You are finally going to try Lenny’s Five Tips for Effective Time Management. The board meeting is next week; it’s not like there will be another one right after it. In two weeks, it really could be over. And you can do anything for two weeks. So lie to yourself that that’s all that’s left.

If there is a unique toll that startups take, it’s that: Go fast, forever. Maintain perpetual urgency. Redline, because speed now compounds later.3 Sow today, reap later. When? Nobody knows, but keep the faith. The finish line—or the rogue wave—is out there, fast approaching.

—

But if you knew where it was?

What if it wasn’t around an unknown bend, but was stamped on the calendar, in permanent ink? What if your company had a Death Clock? What if you knew that there was an exact day that you were going to nuke your Google drive and your Github, declare bankruptcy—on emails, on technical debt, on actual debt, on all of it—and burn the office to the ground?

It is hard to overstate how profound of an effect that this would have on a startup. “We need to survive, indefinitely” is probably the single most important clause in a company’s constitution; changing it may be the most dramatic switch you can flip. Would you run a startup that differently if you never wanted to turn a profit? If you wanted to grow slower? If you wanted to turn a profit as early as possible? If you wanted to work remotely, from nine to five, with eight hours for work, eight hours for rest, and eight hours for what will? These are differences of degree—you’d raise money from foundations rather than venture capitalists, or hire more carefully, or promise less to your customers. But none of this changes a company’s biological imperative: To survive, above all else.

But break that rule, and you change everything.

Providing context

I joined the Harris for President campaign in July of last year, just as it was becoming the Harris for President campaign.4 I applied in late April, trickled through an interview process in May, and then, in June, Joe Biden blew up. I was later told that fifteen minutes into that fateful debate, the campaign watch parties became funerals—heads in hands, desperate texts, people whispering if they should update their resumes. A close race slipped into freefall; the office became a dirge, a living wake for the presumed dead.

By the time I started in July, Biden was out, Kamala was in, and the mood was hopeful. It was brat summer; there were memes; there was money everywhere. We were so back. Though we were never told the precise balance of our internal polls, the rumors were that it was tight. We were within the margin of error, and trending upwards.

I joined the campaign’s data and tech division, a hundred-or-so person department that was run out of downtown Wilmington, Delaware. We worked out of an office called The Mill, and were occasionally referred to as “Mill people” (derogatory). The rest of the campaign, including the romanticized political roles like communications directors, opposition researchers, and senior advisors worked out the Brandywine building, which was best said with a haughty affect and an upturned pinky. True to character, The Mill looked like a startup on a budget, and 🎩 Brandywine 🥂 (derogatory) looked like an Aaron Sorkin set. It was full of posters, split-screen TVs, hustle and bustle, and yelling. We had a couple loose Kamala signs and a mouse problem.

The tech department was split into five or six teams: Pollsters and statisticians, who ran carefully guarded polls that told us _________; data scientists, who turned these polls into forecasts and support models; paid media analysts; fundraising analysts; and engineers, who built our internal tools and kept our infrastructure alive.

I was an analyst on the targeting team. Our job was to aggregate every measure of the campaign’s voter outreach operations—every ad, every text, every door knock—into a giant panorama of “contact.” We ran an ad during an Eagles game, but who saw it? Which voters did that ad reach? We tried to make an educated guess. Cross our ad buys with the demographics of the media markets they were run in and with the assumed audiences of each program, compute the likelihood that a voter was watching when it aired, and roll it all up, by state, by race, by age, by education, by county. Campaign leaders built a strategy around who they thought we should be talking to—from instinct, from polling, from experience; I don’t know, that was a mile above my pay grade—and our job was to tell them who we thought were actually reaching.

Well, rather, it was someone’s job to tell them. It was not my job. Because that is one of the defining cultural features of a campaign: There is an strict hierarchy and reporting chain. Every request was filtered through layers of delegation. Your work goes up a level, then another, then another. It gets discussed, questioned, “decision-ed.” If something needs to change, feedback caroms back down, through Brandywine, across the courtyard between it and us, until it Plinkos its way to the desks of the right Mill people.

For those of us who had come to the campaign from other careers, this was all very weird. Yes, campaigns have to move quickly, and maintaining a militaristic chain of command probably helps keep the organization deft and responsive. But speed is also critical to startups, and they rarely operate this way. And yes, everyone, from journalists to Republican operatives to international spies, is trying to pry and hack information out campaigns; keeping people in airlocked need-to-know compartments minimizes what might leak. Most internal chatter wasn’t guarded that carefully though,5 and we mingled about in an open office.

Instead, it seemed, this was the culture because of something more fundamental: Campaigns are like this because campaigns are short.

At a normal company, you have to invest in employees. You want them to build organizational context; you want them to cultivate cross-departmental relationships. You want them to stretch, to grow, to be more valuable next year than they are this year. They are investments that you want to retain. Managers almost always have some simmering anxiety about their employees’ happiness. Are they satisfied? Are they getting tired of their job, or impatient about their prospects for a promotion? Are they about to leave?

None of this matters on a campaign, especially during its final few months. People don't leave. They do need to be developed or retained; nobody gets promoted. There is no next year. The messiness of team-building—of coaching and career development; of cultivating talent; of helping people build lasting organizational awareness; of balancing autonomy with delegation—is almost entirely unnecessary.6

On one hand, this can be suffocating. On the other hand, it’s enormously freeing. Usually, things like “high-level strategy” and “people and morale management” go together; you cannot do one without the other. Though startup founders often try to offload or ignore one—they fancy themselves as product visionaries or technical geniuses who can’t be distracted by one-on-ones or internal disagreements or listening—this gambit rarely works. Running a company requires both doing stuff and keeping people around who can help do it.

But on a campaign, it’s mostly just doing stuff.7 Obviously, you need to work together, and be a team, and all of that,8 but that team did not need to last. Our only priority was to build a machine that earned us as many votes as possible on November 5th. It didn’t matter what happened to us on November 6th.9

Not like us

This was just one of the many ways that the existence of E-day—election day, erasure day, extermination day—rewires everything about a campaign. When I first joined it, I thought it would be like a bizarro startup: It raised billions of dollars; it grew from a few employees to more than a thousand, in under two years. A campaign is just a startup with the dial turned to eleven, right?

It was not—not because of the “product” we were “selling,” or the nature of our funding, or the mission we were pursuing. It was something entirely different, and that difference overwhelmingly came from one thing: The looming guillotine we were working under.

Which startups can only learn so many lessons from. An irrevocable expiration date is effective because it is irrevocable; you can’t fake it. A stern look and saying, “No, this time the deadline is really important” is not the same thing.

Yet, the effect was profound enough—not always good, exactly, but powerful—that it’s hard not to wonder what a company would be like if it stuck a time bomb to itself.

—

They say that strategy is choosing what not to do. True or not, it’s a useful proverb, because companies love nothing more than not choosing what not to do. They want to experiment, optimize, tweak, reorg, test, launch a tiger team, give themselves a way out. It’s not exactly indecision so much as it’s maintaining optionality.

But there’s no point in maintaining optionality if you know you won’t have time to exercise the option.

“Disagree and commit” is another popular corporate cliché that’s hard to live. Commit for how long? What if it starts to come apart? When do we reconsider? When do we reprioritize our ruthlessly ranked priorities? When can I disagree again? The possibility of eventually decommitting makes a truly unwavering commitment almost impossible. If you know when the company shuts down, all these questions have easy answers: Commit forever; we don’t have time to reconsider; you can’t disagree again.

—

Is hysterical strength—mothers hulking cars off their children, essentially—real? I don’t know.

Is hysterical urgency real? I don’t know either, but I do know that when I started working on the campaign, I thought I was doing things quickly. An executive needed a new report; sure, I’ll get it to you by the end of the day. We need to rebuild this corner of our targeting infrastructure; two days, tops.

Ahaha, no. Deadlines on campaigns are measured in minutes and hours. Canvasser packets are getting printed in three hours; the campaign manager is expecting an updated Google Sheet in two; your boss needs it in 45 minutes. I thought the job was to move fast with stable infra; the actual job was to move fast, tech debt be damned. It was YOLO—You Only Live One more month, and is it really debt if you’re going to delete the whole codebase before the bill is due?

You think startups move fast? You have no idea how fast you can actually go. Campaigns ship at a pace that startups can only dream about. Every day is hack day. Every day is launch day. It’s after midnight; failing tests don’t count after midnight. It’s after midnight; fuck it, I’m casting everything to a string.

Again, this can’t exactly be faked. If you want to build a lasting company, you can’t bulldoze tests and hardcode dates. But necessity—and knowing that whatever heinous hack you do only needs to run for three more weeks—is the mother of a lot of invention and creativity.10 When you’re racing to finish something that might eventually make its way to the Vice President of the United States, you realize that your old idea of going as fast as you can really meant going as fast as you thought was reasonable and comfortable.

—

At a startup, late nights can percolate into toxic resentments. Have one all-nighter, sure, it happens. Have two, and people start to point fingers. Who's fault is this? What process broke; which executive isn't looking out for us? Even if you aren't the target, you can feel the frustration: People want to go home, and tomorrow, things better get fixed.

On a campaign, the vibe is different. This is all going to be over in two months, and holding a symposium of retros on how to fix a process will be more work than just plowing through it. We're here, trapped in the belly of this horrible machine, and we might as well make the most of it. We are all waiting for a massive data pipeline to run at 1am; might as well put the Airflow DAGs on an 80-inch TV and bet on when each job will finish.

Could we have done more to get people home earlier? Could meetings have been more aggressively streamlined? Could we have been more mechanically productive, turned more meetings into emails, and squeezed more slack out of our days? Probably. But there is overhead to this; vigilance requires energy too. Always asking, “How could this be better?” is not free. And if you know time is short, there’s often more serenity—and outright productivity—in accepting that some things that could be changed simply aren’t worth changing.

—

Most obviously, a death date makes a hard job much, much easier. To keep the operational machinery of the campaign running, we were at the Mill, all the time. By September, Saturday had been officially annexed as an in-office workday.11 One coworker routinely joked that his goal was to be out of the office by 11 pm; he rarely made it.

It was a lot—easily as time-consuming as any sprint in Silicon Valley, and sustained for far longer. But you never had to wonder where the finish line was, or if this break in the clouds would last. You never had to lie to yourself about holding on for two more weeks. You knew: It will be over in 84 days. In 9 days. It will be over tomorrow. You really can do anything for two weeks, or even 84 days, if you know that there’s no hope that you’ll only have to do it for 83 days, and no chance you might have to do it for 85. Uncertainty, it turns out, wears you down much faster than effort.

This is water

There is one more thing.

It is so easy to become obsessed with “forever.” Companies endure, or they’re a failure. Relationships last ‘til death do them part, or they’re a disappointment. Legacies are so often defined by how long something lasts; by whether or not they “make it.”

The campaign was not asking us for a lifetime, just for a minute or a night. And to start on something that you know will end is to be liberated from worrying if it will work. Don’t overthink it. Don’t wonder if there is a better decision out there, or if this is “the one.” It is over, on exactly November 5th. They are leaving, soon. Live in the cherished moment, recklessly.

Of course, we all know this cheesy lesson: Carpe diem; live like there’s no tomorrow; you only know what you have when it’s gone. It’s the sort of cheap wisdom that is in every beach read about teenagers with terminal cancer—not exactly profound stuff.

But it is hard to see how captured we are by the imperative to survive—how held we are by its gravity—until you live on a timeline in which there isn’t one. Worrying about the future is so natural and so ubiquitous that it hides in plain sight, paralyzing us, making us cautious, and overweights every decision. We ask ourselves if something is safe. We wonder if this is good enough for “forever.” We rationalize that it’s not. We look for faults and flaws and signs of danger, because one bad choice could have lifelong consequences.

Lifelong means something different under a catastrophic wave. Shallow platitudes find a new depth beneath a pounding surf. That is the subtle tyranny of our untimed mortality: We are blind to the wisdom of these clichés, and the mistakes we make by ignoring them, because you can’t live like you’re dying until you’ve lived knowing you’re dying.

The White Lotus Power Rankings

Saxon finally loses his crown, and Fabian debuts way too low:12

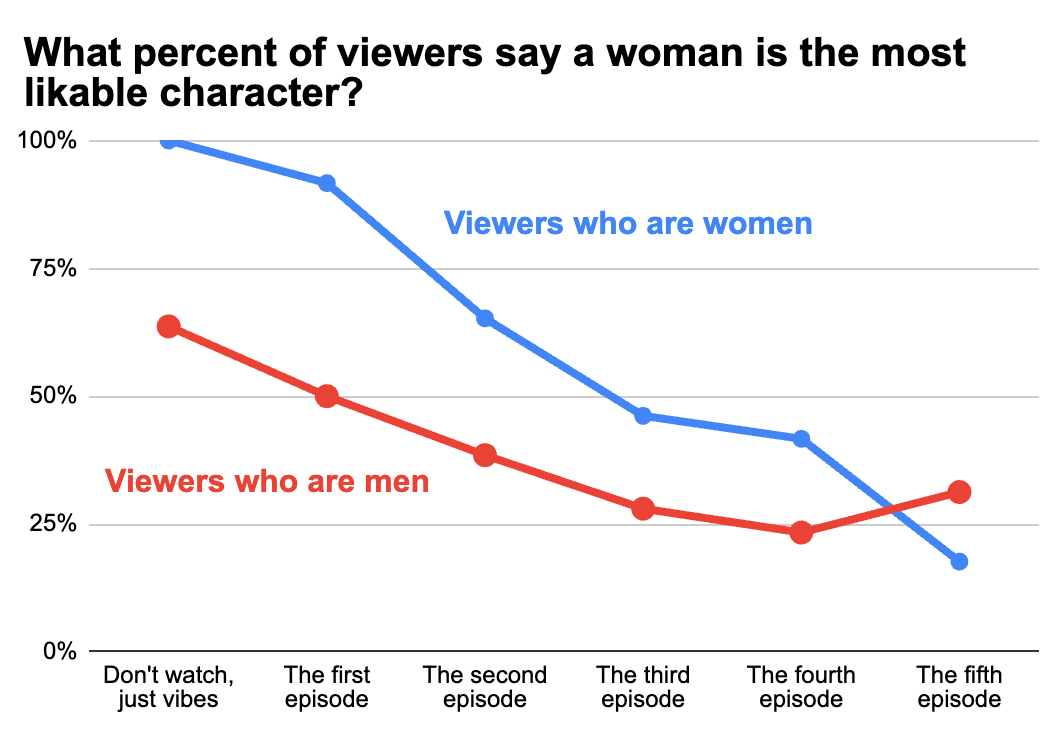

One of the other things that stood out in the early votes was the gender split—men liked men, and women liked women. The women have steadily been getting less popular, and after the fifth episode, the gender split has now reversed:

Vote for episode six! Analyze the data yourself! Don’t go to that party at Greg’s house!

One way to look at raising money is that a VC check is a prize to keep playing a game that you’re doing well in, like finding a bunch of extra lives in a video game. Another way to look at it as a huge slug of debt, collateralized by your job, with a tacit APR of about 250 percent. If you walked into Chase, asked for a $10 million dollar loan, and they said “sure, here, now you owe us $25 million in a year,” you wouldn’t have a party; you’d have a panic attack.

IPOs, like funding rounds, are performative beginnings.

Not only is it important for a startup to go fast; it’s also important for a startup to go fast now. It’s two extra derivatives of urgency: Running a mile today is worth a dollar. Running two miles is worth three dollars. But two miles tomorrow is only 50 cents. And one mile tomorrow is worthless; you might as well not even bother.

My email address was still for joebiden.com.

Admittedly, there’s also another dynamic here. If your career is campaign work, “promotions” typically happen across election cycles. You work as an analyst in 2024, your ambition is to be a lead or director in 2028, and an executive or special advisor in 2032. But there’s only one big campaign at a time, and only a few of these seats on each campaign. Though everyone’s first incentive is to win the election—both because I think most people’s motivations are honest, and because winning is good for your career—their second incentive is to position themselves well for the next election. Your coworkers around you are your coworkers, but they are also your most direct competition. Maintaining organizational hierarchy helps protect your position on the totem pole. It’s not cutthroat, per se—again, I think people are largely well-intentioned—but it is a dynamic that doesn’t exist in the corporate world, because there are lots of other places you can work. There are many other totem poles.

In other words, on campaigns, there can be a lot more personal incentive to manage up than down, especially when compared to jobs elsewhere.

And it’s pretty fun?

Obviously, what happened on November 6th, and in the months after that, has, uh, mattered a lot. In that sense, campaigns clearly have longer and louder echoes than most companies. The point here is the work of building and working for a campaign has a tight expiration date, not that campaigns cease to matter the day after election.

For example, in our efforts to mash together data on our ad buys, we had to orchestrate a number of large data pipelines with a somewhat complicated series of triggers. One proposed solution: What if, instead of building an orchestration algorithm, we just figured out all the dates it needed to run, wrote them down, and had the pipeline run off of a hardcoded list?

There was some debate about what to call this extra workday. Did the week now have two Tuesdays? Two Wednesdays and no Sunday? Someone settled on the week having six Thursdays—a day you’re tired, but still have a ways to go—and one Sunday.

Last week, I said that Tim was mysteriously falling in the murderer rankings, and that that didn’t make any sense. Well, mystery solved: I forgot to update the names on that chart from the prior week. It turns out, the corrected table would’ve shown that Tim had actually moved up to the top spot. Apparently, every day is hack day here at benn dot substack dot com too.

Your best yet. Thank you Benn!

Another great post. Obama 2012 had a countdown clock I looked at easily a dozen times a day:

https://x.com/MichelangeloDA/status/1906008022205305024

Would love to compare notes someday.