Maybe, finally—the end of SQL

Vibe and verify.

Five or six years ago—maybe you forgot? Maybe you are trying to forget?—there was something called the “data industry.” It was a collection of tools, philosophies, and people that worked with databases to make dashboards and find insights about their businesses. At its best, it was a generous community of people with similar careers and hobbies; at its worst, it was a pyramid scheme of Ponzi schemes selling vaporware to one another.1

Five or six years ago—maybe you forgot? Maybe you are trying to forget?—there was something called “Twitter.” It was an internet website. At its best, it was a fun chat room for people to talk about their careers and hobbies. At its worst, it was a place for people to sell you stuff from their latest Ponzi scheme.2

Anyway, back then, there were two topics that would inevitably get the “data industry” riled up on “Twitter.” One was to declare, unambiguously, that data teams should be centralized within their companies and report to a vice president of data. Or that they should be fully decentralized, and some of them should report to the head of marketing, and some to the chief technology officer, and so on.3 It didn’t matter which side you took; half of the people on Twitter would get mad.4

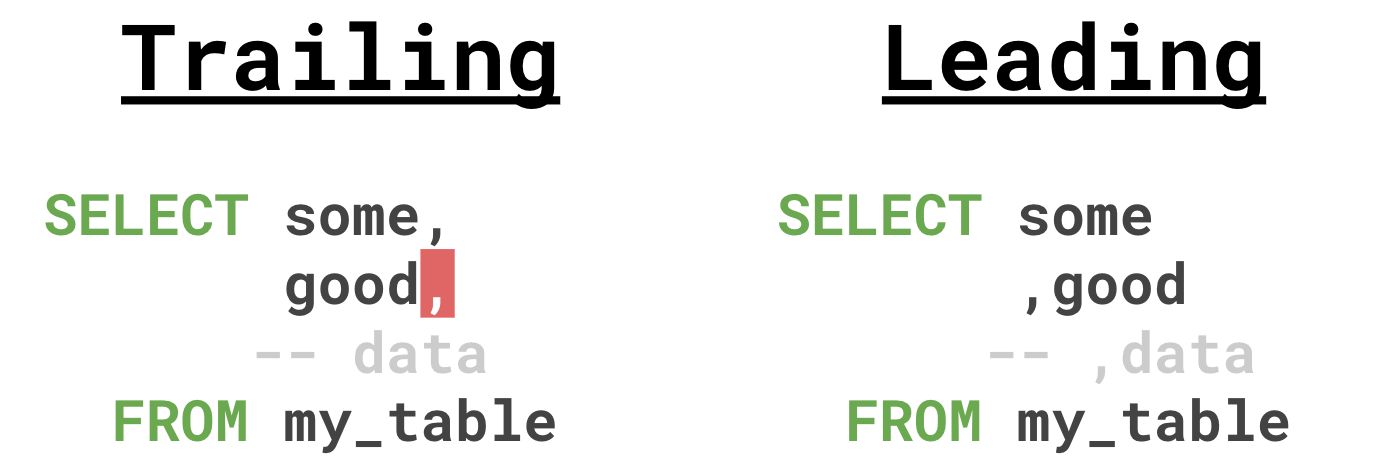

The other topic was commas. People who work with data write a lot of SQL, and SQL queries have a lot of comma-separated lists. The items in the lists are often written on separate lines. Some people preferred to put commas at the end of every line, since that’s how most standard prose would look. Others preferred to put commas at the beginning of each line, because you could then delete the line without orphaning the comma from the previous line:

My contribution to the debate was, charitably, a poem:

While leaders lead with leading commas, and trailing commas are leading signs of failing lines, and the tale aligns no matter the database breed, we’re not agreed that it’s best to concede to lead because the more we scale our query kneading, the more we follow the trail to trailing from leading.

Because it’s people, who do the reading.

Of course, this was all very dumb; everyone knew that; that was the whole point. It was turpentine, or cope, or a way to entertain ourselves while our queries ran.

Still. The whole argument did represent at least one substantive point, summarized by that last line: That reading and writing are not the same thing—and, especially, reading and writing code are not the same thing. If you are writing SQL, leading commas are probably better, because they make it easier to add and remove new lines. You could quickly change a query like the one in the example above, and not worry about your edits causing the query to fail. “I spent thirty minutes trying to figure out why a query was broken, and it was a rogue comma the whole time,” many people have said. Leading commas make that less likely.

However, if you are reading SQL, leading commas are unaesthetic.5 They are a clumsy eyesore; a wrench in our fast-moving visual gears. They are great for development, but bad for comprehension.

And it’s not just commas; this is also true for dozens of syntactic and stylistic choices. When we write SQL—and any other sort of code, I imagine—there are all sorts of conveniences that can speed us up. We can use functions for processes that we repeat all the time. We can use abbreviations and notational shorthand to write faster. We can combine complicated, multi-step operations into one. These things save us a lot of time, because we have to type less, and because typing less means fewer chances to make mistakes.

But these shortcuts also make SQL harder to understand. We’ve talked about this before: Functions and abbreviations are abstractions, and “an abstraction is a layer cake of logic;” it is “a lever with many strings attached to it. These are complex things with many moving parts,” and eventually, this complexity overwhelms us. If we want to write something, abstractions are useful. If we want to understand something, abstractions are often bad. Instead, a bunch of simple words—and a picture, even—is often much more effective than a succinct technical description.

Five or six years ago, that was the tradeoff. Write SQL in a way that was easier to write, or write SQL in a way that was easier to read. And because we had to write SQL in both cases, we often chose to write in a way that was easier to write.6

But it is now 2026. And, you know:

“~40% of daily code written at Coinbase is AI-generated.”

“About a quarter of the recent YC batch wrote 95%+ of their code using AI.”

“Every single line was written by Claude Code + Opus 4.5.”

“YOLO. Diffs scroll by. You may or may not look at them.”

“These days I don’t read much code anymore.”

That’s the future of software development, it seems. Tell a robot to update something, wait for it to finish, and push some buttons to see if it works the way you want it to. In about a year, engineers went from mostly writing code, to reading code, to just testing code. Write and read, to vibe and verify.

Can data people do that, though? Can we barrel through our backlogs in the same way? Ehhh:

When people talk about the challenges associated with automating analytical work, they often talk about making sure agents have the right data and context to answer questions correctly. The far bigger problem, however, seems to be that there’s no way to know if the work is right. You can’t click around a chart to see if it works like you can on a vibe-coded app. You can’t vouch for a spreadsheet without checking all the spreadsheet’s formulas. All you can do is either read through the code, line by tedious line, or recreate the whole thing yourself. And if you have to do that, what exactly are we automating here?

Six months ago, this problem seemed like an annoyance. Now, when everyone else who works with a computer is locking in in front of an IMAX of Claude Codes, like Ender, or Batman, or a WallStreetBets day trader, manually reviewing code feels existential. Quantitative analysis is on shaky ground already; how much faster will it fade into obsolescence if the new magic that works for everyone else doesn’t work for us?

Maybe there is a solution, though—we rearrange the commas.

When AI generates code, we don’t need to read exactly what it wrote; we just need to understand it.7 One way to do that is to stuff a query into ChatGPT and tell it to explain it, which people periodically try to do. Unfortunately, that’s probably a dead end: Queries contain dozens of tiny computational details that are both painfully imprecise to express in English, and painfully hard to understand in prose. But the choices aren’t necessarily just raw SQL or paragraphs of text. There could be other representations too: Better formatting, with commas arranged for reading. A different language, designed exclusively for comprehension. Diagrams, mapped and annotated. A logical explain plan, and maybe even a picture.

Of course, new query languages and visual SQL editors have existed for a long time; a thousand BI tools have sworn they would never visit that hill, and then died on it later. But these things have almost always been built to help people who do not know SQL write SQL. The thing we need is neither of those things. It is a tool—a language? An interpreter? A app?—that helps people who do know SQL read SQL. It is for verification—what did this query do?—and annotation—update it, doing it this way.

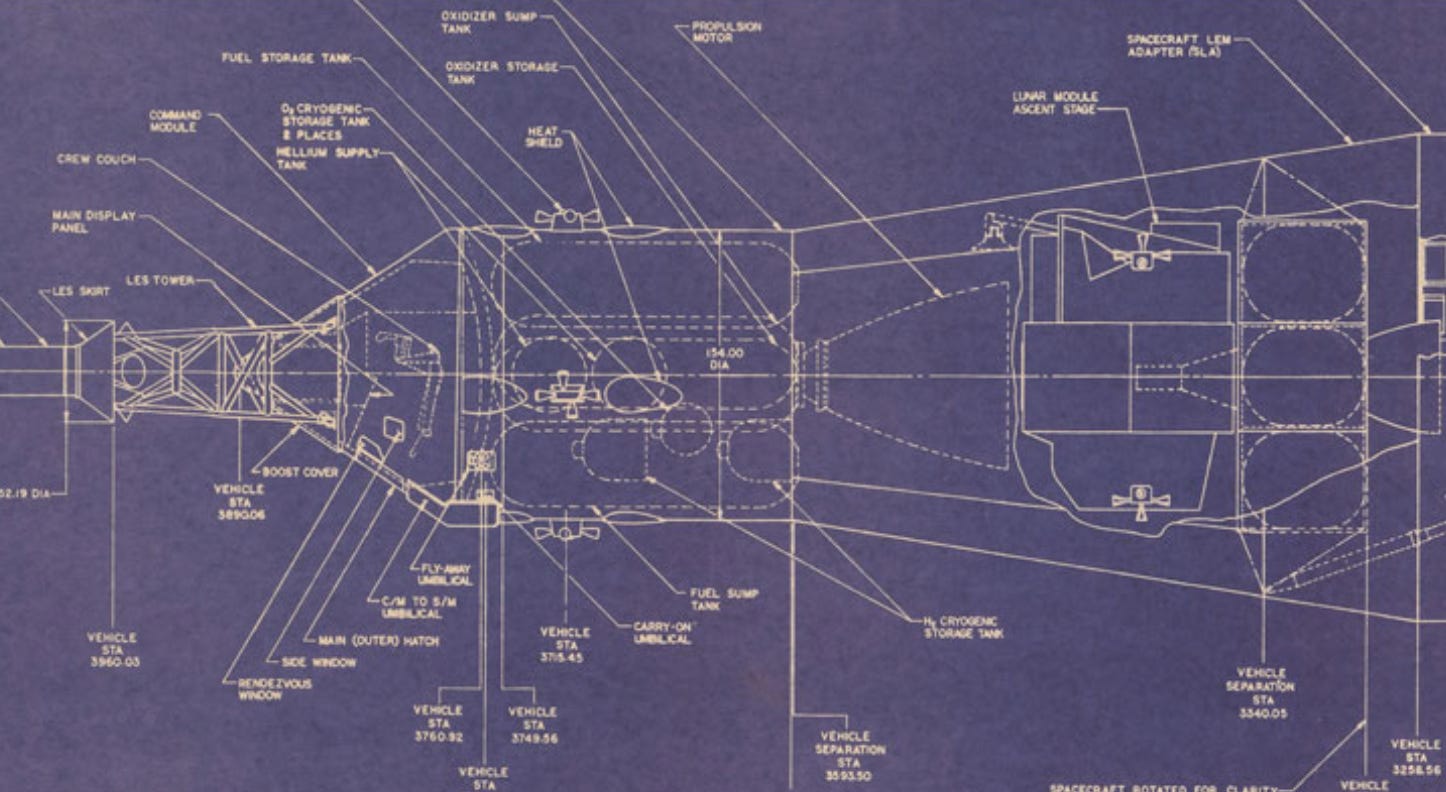

At first glance, this has similarities to a semantic layer, as both are simplifying representations of complex underlying queries. However, semantic layers transpile in the wrong direction. They turn formulas—formulas full of buried abstractions—into structured queries. We need the opposite: Something that turns an arbitrary query into an accessible diagram. I don’t want dropdowns to generate a complex query. I want to ask a robot to write me any query I can think of, and a picture and some words that tell me how the big computer did numbers.

—

Actually, no; there was also a third way to goad people into fights on Twitter: By talking about languages. Python or R? SQL or Python? Pandas or Tidyverse? White dress, or blue?

Wes McKinney—the creator of Pandas, and someone who’s as responsible as anyone for Python’s popularity with data people8—recently said the answer may be none of the above:

Human ergonomics in programming languages matters much less now. The readability and simplicity benefits of Python help LLMs generate code, too, but viewed through the “annealing” lens of the iterative agentic loop, quicker iterations translate to net improved productivity even factoring in the “overhead” of generating code in a more verbose or more syntactically complex language. …

The winners of this shift to agentic engineering are the languages that have solved the build system, runtime performance, packaging, and distribution problems. Increasingly that looks like Go and Rust.

For analytical code, the debate about languages was almost entirely about ergonomics. Most people liked one language over another because of how it felt to write. With enough massaging, Python, SQL, R, Julia, MATLAB, SAS, and just about any other language can do just about any math you want it to. The concern, then, was about how hard it was to express that math.

We now have robots for the writing, and we can compel them to write whatever tedious thing we want.9 But for analytical work at least, people still need to do the reading.

Imagine, though, if there were diagrams or an app that could make just one of these languages more legible. Imagine if we could check the math as fast as ChatGPT can do the math. Imagine if we too could vibe and verify. If that existed, and data Twitter were still a Thing, what would we lose our minds about then?

Arguably, there were three Ponzi schemes stacked on top of each other. Startups are often designed not to make a little bit of money for a long time, but to be sold to someone for a lot of money all at once. Data teams long promoted their value by promising future value, once better tracking was in place or all the basic dashboards were done. And a lot of data startups were companies that hoped to sell that promise, first to customers and eventually, to a future acquirer.

That is how you get stock charts like this, I suppose.

ahaha, lol, if only this was actually Twitter at its worst.

There was a third option, which was a “center of excellence,” but if you said that, you would reveal yourself to be either Gartner or, worse, from LinkedIn.

Though you could not say they should report to the CFO; that made everyone mad.

And every analyst should be at least 50 percent vain.

For engineers, they have a proxy for that understanding: The software itself. If the buttons work, they understand what the code does. Kinda. Sorta. But, enough.

And the creator of a website that can save you from the tiresome drudgery of this blog by automatically giving you the CliffNotes (and, more usefully, by directing you to other blogs that you should probably be reading instead).

Data analysis is one of the only things I'm not comfortable trusting AI to do, which makes sense since I'm a Data Person. I have found ways to use AI to speed up and enhance the data analysis process, like feeding it little bits and having it just do that bit. But handing it a whole dataset and saying "go to town, tell me what's up?" That ways lies madness, or at least nonsense. But then, I imagine that's how many people feel in other disciplines about using AI for what they do.

"We need the opposite: Something that turns an arbitrary query into an accessible diagram. I don’t want dropdowns to generate a complex query. I want to ask a robot to write me any query I can think of, and a picture and some words that tell me how the big computer did numbers."

Yes, this would be wonderful. I've thought about this over the years - especially when handed someone else's complex SQL and I need to understand what it's doing.