Pure heroin

A different kind of buzz.

If you asked me why this blog exists, I couldn’t tell you. Though it often repeats itself, it is not here to make any particular point or achieve any particular ends. There was no central reason why it began, and there won’t be one for why it ends. It has no serious purpose; it is only here to sing or to dance while the music is being played.

That is: It’s entertainment, more or less. The world is full of interesting things, even in this erratic corner, and they are more interesting—and entertaining—to look at together. And so we are here: We hang out; we go home; I hope you had fun.

Still, there are lapses. Attention is a hell of a drug, and as you do something like this, you develop a loose intuition about the sorts of things that attract it. And sometimes, you give in to temptation.

That is the existential corruption of the internet, both for the people who use it and the companies that make it. Start honorably; get addicted; step out. Substack, for example, initially promised that “publishers will own their data, which we will never attempt to sell or distribute, and we won’t place ads next to any of our own or our customers’ products;” last week, they began piloting native ads and forcing mobile readers to download their apps. And, partly in service of those goals, they show me dashboards of engagement metrics and give badges to their most popular writers; I get hooked and chase those, too.

It’s Goodhart’s law for social media: When a good becomes a metric, it ceases to be good.

But, this is old news. We know that this is how social media works. We’ve talked about this before:

In direct and indirect ways—by liking stuff, by abandoning old apps and using new ones—we told social media companies what information we preferred, and the system responded. It wasn’t manipulative or misaligned, exactly; it was simply giving us more of what we ordered.

The industry refined itself with devastating precision. The algorithms got more discerning. The products got easier to use, and asked less of us. The experiences became emotionally seductive. The medium transformed from text to pictures to videos to short-form phone-optimized swipeable autoplaying videos. We responded by using more and more and more of it.

And now, we have TikTok: The sharp edge of the evolutionary tree; the final product of a trillion-dollar lab experiment; the culmination of a million A/B tests. There was no enlightenment; there was a hedonistic experience machine.

We know that this type of internet—one dialed to optimize engagement—can tear us apart in thousands of ways. It can make us miserable; it can make us dull; it can make us self-obsessed; it can make us murderers. It can destroy a generation. It can destroy a democracy. Everyone from the U.S. surgeon general to Heineken is worried about it.

But what do you do? Social media is too big to regulate, too integrated to remove, and we are too addicted to want to do either.

Anyway. What does OpenAI do? Roughly speaking, they build two things:

A suite of generative models that can convincingly mimic highly intelligent human behavior.

A chatbot.

Sure sure, this is all very reductive and imprecise—the chatbot sits on top of the models; the models use data from the chatbot to improve; OpenAI makes other products, like web browsers and computer chips and data centers and creative corporate financial solutions. But, as far as core services go, these are two big ones.1

Of course, you could label them differently. You could call one “research” and the other “applications.” Or, more stylistically, “safe and beneficial AGI” and “commercial products.” Or, even more stylistically, a “mission” and “money”—according to some reports, about 80 percent of OpenAI’s revenue comes from ChatGPT subscriptions.

And for OpenAI, there are some natural tensions between the two:

Even as ChatGPT attracted more users this year, improvements to the underlying AI model’s intelligence—and the in-depth research or calculations it could suddenly handle—didn’t seem to matter to most people using the chatbot, several employees said. …

The company’s research team had spent months working on reasoning models that spent more time computing answers to complex questions about math, science and other topics than ChatGPT’s previous models. … Most of the questions users asked ChatGPT, though, didn’t take advantage of those types of improvements. …

Much of the time, ChatGPT users are “probably asking about pretty simple things, like movie ratings, where you wouldn’t need a model to think for half an hour.”

If you are trying to replace Google with an omniscient chatbot, you first worry about how smart the chatbot is. When people ask, “how long does it take to caramelize onions?,” it can’t blithely tell them “five to ten minutes,” and it definitely can’t get confused and give them reviews of Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery. They will stop using your chatbot. But once your models are smart enough to solve that problem—once they can not only tell people how to caramelize onions, but can also give them an entire menu for their dates—more intelligent models might not make it more popular. It’s cool—and maybe good for humanity?—if your chatbot can solve the world’s hardest brain teasers. But people use it, and pay you $20 a month for it, because they like the UI and remember the URL.

When everything is booming, these two ambitions—superintelligent models and delightful chatbots, or research teams and product teams, or benevolent AGI and financial prosperity—can peacefully coexist. You can do everything. You can spend $6.7 billion on research and development, and another $6.5 billion on famous product designers. You can have a mission and a business. And, as we’ve talked about before, you can sacrifice a bit of money for the sake of your values:

Most people don’t want to lead or work at companies that are singularly motivated to make money as ruthlessly as possible. Most people would prefer some moderation—they would trade some corporate profits for better employee benefits, or cleaner factories, or promises to treat customers respectfully. Most people also care about how their employer tries to make money. … Though these ideas necessarily put constraints on how much money a company can make…it’s a deal that most people, including founders, executives and boards, want to make.

But, you know:

Everyone knows that if Airbnb [or OpenAI, or whoever] isn’t making enough money, it will fire a bunch of people and tell others they need to work more. Everyone knows that making money—at least enough to survive—will always be more important to Airbnb than how it makes that money.

When you commit to spending $1.4 trillion over the next eight years, as OpenAI has, making enough money to survive means making a lot of money.2 So, when people start loudly abandoning your chatbot, or declaring your competitors’ products as better than yours “and it’s not close,” the tensions between solving novel math problems and building something that a billion people3 want to buy quickly become real:

When OpenAI CEO Sam Altman made the dramatic call for a “code red” last week to beat back a rising threat from Google, he put a notable priority at the top of his list of fixes.

The world’s most valuable startup should pause its side projects like its Sora video generator for eight weeks and focus on improving ChatGPT, its popular chatbot that kicked off the AI boom.

In so doing, Altman was making a major strategic course correction and taking sides in a broader philosophical divide inside the company—between its pursuit of popularity among everyday consumers and its quest for research greatness.

OpenAI was founded to pursue artificial general intelligence, broadly defined as being able to outthink humans at almost all tasks. But for the company to survive, Altman was suggesting, it may have to pause that quest and give the people what they want.

And specifically, Altman wants to turn the dial to optimize for engagement:

And it was telling that he instructed employees to boost ChatGPT in a specific way: through “better use of user signals,” he wrote in his memo.

With that directive, Altman was calling for turning up the crank on a controversial source of training data—including signals based on one-click feedback from users, rather than evaluations from professionals of the chatbot’s responses. An internal shift to rely on that user feedback had helped make ChatGPT’s 4o model so sycophantic earlier this year that it has been accused of exacerbating severe mental-health issues for some users.

Now Altman thinks the company has mitigated the worst aspects of that approach, but is poised to capture the upside: It significantly boosted engagement, as measured by performance on internal dashboards tracking daily active users.

We have seen how this goes. We’ve seen what happens when social media becomes a metric, and we’ve seen how seductive chatbots can be when they want to be engaging.4 Moreover, AI isn’t “just” social media—the chatbots sit on top of the models, the models learn from the chatbots, and the models are replacing all of our software. OpenAI’s turn towards engagement doesn’t just alter our interactions with ChatGPT; it potentially alters our interactions with everything:

AI is surely becoming a new invisible hand pulling the levers in our minds. It is some inscrutable new force that’s writing the first draft of history. It’s interpreting our data; it’s creating our websites; it might soon summarize our emails and brainstorm our ideas and suggest our dinners and mediate our relationships.

OpenAI is already too big to fail. What happens when it becomes too integrated to remove? What happens when the mission becomes less important than the drug? What happens when we become too addicted to care?

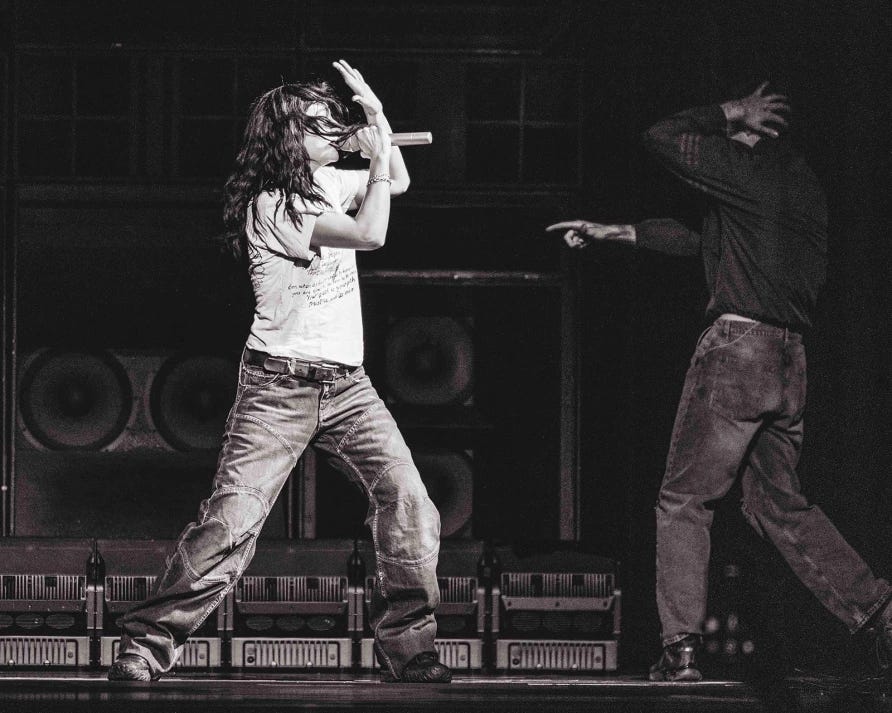

I saw Lorde a few days ago at the Barclays Center in Brooklyn. I was sitting in the upper deck, a couple of rows from the front and a few seats from the aisle. At the end of the aisle, there was a small overlook, with a clear view of the entire arena.

Throughout the show, groups of teenagers and twenty-somethings took pictures of each other standing in front of the overlook. Each group took dozens of pictures—individual pictures, different pairings of friends, different angles, live shots of people cycling through poses, one picture immediately after the other, like a model in a shoot. One group turned into a lighting rig—a girl took pictures; another stood a few feet to the side, with her phone’s flashlight angled slightly away from the main subject; a third stood behind the camera, partially covering her flashlight with her fingers, creating a makeshift diffuser. Several girls cycled through twice, evidently unhappy with their first shoot. And twice, when a group wanted pictures of everyone together, a girl across the aisle from me was recruited to be their photographer. She instinctively gave the same practiced stage direction. “Pull your shoulders back; look more to the left; let your jacket hang lower.” There was something almost poignant in it—a kind of solidarity, where every teenager understood what it took to survive.

That’s the world our metrics made—one in which we don’t sing and dance when the music is being played, but take pictures of ourselves instead. One in which we go to shows not to watch, but to perform. One in which we never bother to take in the view behind us, because we’re addicted to the camera in front of us.

We’re doing it all again. Though we don’t know exactly how this will play out—and it will likely create a different kind of buzz5 than social media did, and be more complex than “people date their chatbots”—we know how addicting attention can be. We know how tempting it is to seclude ourselves in our own realities. We know the dangers of rewiring society on top of technologies that are optimized to be perpetually engaging. We know how much money OpenAI has to make. We know what happens when companies feel backed into corners, and have to decide between survival and their supposed values. We now know how OpenAI responded to their first “code red:” to immediately up our dosage, and see if we might buy more.

I use AI every day. I like it; my life is increasingly dependent on it; the rest of my career will probably be built around it;6 if I could use it to pump some Substack numbers and collect7 a few badges, I would be tempted to do that too. But at what cost?

This blog is prone to melodrama, so let me ask it plainly: What is the plan here? To have faith that it will all work out? To do nothing? To get the bag and get out? To trust that the people in charge will do the right thing? To apologize later, when we’re standing in the rubble? Or to just hope—to hope that we’re handing the world over to something that will save us, and not to a drug dealer that’s a trillion dollars in debt, and selling a cannon of pure heroin?

The three divisions with the most open roles at Anthropic are “AI Engineering and Research” and “Product Engineering and Design”—and “Sales,” because the third thing that AI companies do is incinerate money.

According to estimates from Tomasz Tunguz, they need to make about $600 billion in 2029, which is more than every company in the world other than Walmart and Amazon.

Even if a billion people bought ChatGPT for $20 a month, OpenAI wouldn’t be halfway to $600 billion.

In an earlier post on this topic—this blog often repeats itself—I asked if people supported banning or limiting general chatbots like ChatGPT. Fifty-seven percent of people said we should already be doing this, 37 percent said we might need to do it in the future, and 6 percent said no.

This originally said earn, but, would it be?

Well said, Benn.

Benn, I share your concern about engagement optimization corrupting OpenAI's mission - I watched the same thing happen to Facebook through Steven Levy's book. Mark Zuckerberg really did start out wanting to connect the world, but engagement metrics drove everything.

But your question "what's the plan?" has answers at three levels:

As individuals: We're already seeing the vanguard figure this out. Gen Z's social media time dropped 10% from its 2022 peak - the first time that line has ever gone down (https://appedus.com/gen-z-social-media-decline-great-unplug/). 44% of teens cut back in 2024. The newsletter boom you're sitting on shows people wanted a different way to consume information. Some will fall for the drug, but the ones who make society move are the ones who don't. In the AI age, that means continuously educating yourself - even using AI to help with that - to maintain your own agency.

As builders: This is where I'd challenge you. You and I aren't spectators here - I've been building software since 1981, you've been writing about data and AI for years. We need to figure out what we can build that acts as a counterweight to the drug. I'm trying to build tools that help people be lifelong learners. As you find your next mission, the responsibility is the same - build something that pushes back against the addiction.

Societally: Every technology generates a moral panic. TV would make us passive (it didn't). The web would make us stupid because all the answers were there (it didn't). We're seeing real harms from social media, yes. But most technologies have enhanced our lives more than detracted from them. The question isn't whether AI will cause problems - it will. The question is whether we're building the counterweights.

We've been here before. We're starting to move away from social media's worst excesses. We'll do it again with AI.